What you’re not paying for medicines

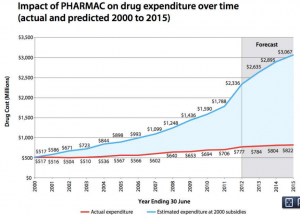

From Pharmac’s annual report for 2012 (via @sudhvir), a graph comparing actual government expenditure on subsidised drugs (red) with what would be projected under pre-Pharmac subsidy policies (blue)

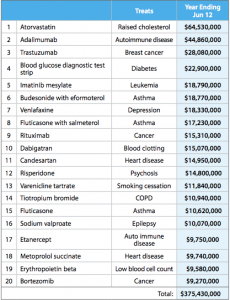

This table from the report shows some of how this was done. It shows the twenty drugs on which the most money was spent

Many of these are new (any drug whose name ends in ‘b’ is likely to be new), but they are mostly drugs that are genuinely better, at least for a subset of patients, than the alternatives. The top of the list, atorvastatin, lowers cholesterol more effectively than the cheaper simvastatin. It’s the best selling drug of all time, but in New Zealand is used only in a relatively small set of people whose cholesterol doesn’t go down enough on simvastatin. Adalimumab was a breakthrough in serious rheumatoid arthritis, and trastuzumab is the revolutionary breast cancer treatment sold as Herceptin.

Further down the list, candesartan is a blood pressure drug that can be used in people who have side-effects with some other blood pressure drugs. In Australia, candesartan and its relatives are used very widely; here they are used only when other drugs are insufficient or not tolerated.

Pharmac isn’t perfect, and I think it’s underfunded, but it does a very good job of getting most of the benefit of modern pharmaceutical medicine at a very low price.

Thomas Lumley (@tslumley) is Professor of Biostatistics at the University of Auckland. His research interests include semiparametric models, survey sampling, statistical computing, foundations of statistics, and whatever methodological problems his medical collaborators come up with. He also blogs at Biased and Inefficient See all posts by Thomas Lumley »

Why the b endings for new drug names?

11 years ago

Mostly a feature of them being “mab”s or antibody therapies, and tho bortezomib [(1R)-3-methyl-1-({(2S)-3-phenyl-2-[(pyrazin-2-ylcarbonyl)amino]propanoyl}amino)butyl]boronic acid (thanks wiki) isn’t a mab, it’s relatively new having been approved for use since 2003.

Yay Pharmac btw.

11 years ago

Yeah, -mab from monoclonal antibodies is the big one on this list, but there’s an increasing collection of -ibs: -zomib for proteasome inhibitors, -tinib for tyrosine kinase inhibitors, and others. It’s not the only marker of newness (-or is pretty good), but it’s a remarkably powerful one.

11 years ago

The assertion that “… atorvastatin, lowers cholesterol more effectively than the cheaper simvastatin. ” would be hard to prove. The efficacy (i.e. maximum ability to lower lipids) for these drugs has never been evaluated because its too dangerous. Some trials have used large doses of atorvastatin to get lower lipids but these are associated with a higher risk of serious adverse effects like rhabdomyolosis. Sensible use of statins involves titration to the desired lipid level. I know of no evidence that atorvastatin is more effective than simvastatin when used in this way. Nor that muscle adverse effects are more common when titratated to similar lipid levels.

11 years ago

I agree that it’s hard to say if atorvastatin would be different from simvastatin at equivalent dose, but it was more effective at reasonably standard doses and safer than the very high dose of simvastatin that has also been tested.

There’s pretty good evidence, I think, that pravastatin is safer and that cerivastatin is more dangerous, but apart from that it’s hard to tell.

The biggest problem with titration is that you can’t do it very well because of the measurement noise. Les Irwig’s group in Sydney has looked at this issue for a number of interventions.

11 years ago

Comparing effectiveness and safety of different drugs is only rational when comparing equi-effective doses. Comparing across trials using different drugs and different doses is a game used by drug marketers but it is not a sensible way to describe their clinical pharmacology. That’s why PHARMAC has clinical pharmacologists to advise it.

I am not familiar with Irwig in Sydney – perhaps you could provide a reference to the work you are thinking of. But I don’t see why measurement noise is a problem because I am sure you know repeated measurements will reduce the noise so that it is no longer a problem.

Titration to target total cholesterol concs was a key feature of the famous 4S study which demonstrated the distribution of doses needed for effective lipid lowering.

Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study Group. Randomised trial of cholesterol lowering in 4444 patients with coronary heart disease: the Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study (4S). Lancet. 1994;344:1383-89.

11 years ago

It might be reasonable to argue that in a perfect world the manufactured doses do not matter and only equi-effective doses should be compared, but in reality people are much more likely to take a small multiple of the fixed manufactured dose, and evidence from trials is available on these fixed doses. One could try to appeal to pharmacodynamic models to interpolate, which would probably be ok for effectiveness, but for safety I don’t think the pharmacodynamics is known that well.

Katy Bell is the lead author on the monitoring/dose papers :http://www.crebp.net.au/?page_id=666

The situation is worst for blood pressure, where the signal:noise ratio is so much lower that some patients’ BP appears to increase after treatment, but the same sort of problem occurs with statins.

11 years ago