A bit more complicated than that

On Twitter, I got a link to a Telegraph story “One glass of wine increases stroke risk by third”, with the request “Debunk please.”

Not all depressing health news is necessarily wrong. However, even if it’s describing a real risk you can be pretty confident that it will have been exaggerated a bit, and that’s the case here. It’s probably true that alcohol consumption at not-particularly-high levels increases stroke risk, but it does pay to look more closely at what the research is claiming.

The first thing to notice is that the story shifts from

Middle aged drinkers who down just one large glass of wine a day increase their risk of stroke by a third, warns a new study.

to

The results showed drinkers in their fifties and sixties who had at least two alcoholic drinks a day…

That is, the research lumped together everyone who averaged two or more standard drinks per day (actually, 2.4 standard drinks/day in NZ units). This group, collectively, had a 34% higher stroke risk than the 0.5 drink/day group, but the group who had 1-2 standard drinks per day were not at any increased risk. Unless there’s a magic threshold at 2.4 drinks/day of alcohol, the excess risk must be less than 1/3 for people just into the 2.4+ drinks range, and more for people far into the range.

The next step is to try to look at the actual alcohol consumption in each group, to see how far above 2.4/day the highest group was. That’s not given, but some interesting things are. First, only 3% of the people who had strokes drank more than 2.4 drinks/day, so this wasn’t a very good sample for looking at heavy drinking. The researchers pointed this out themselves: “A potential limitation of our study could be a low proportion of heavy drinkers as alcohol consumption in Sweden is one of the lowest in Europe”

What’s more surprising is that 3% of the people who didn’t have strokes also drank more than 2.4 drinks/day. In fact, the mean and median alcohol consumption were slightly lower in the people who had strokes than in the people who didn’t. How can this be?

Part of the explanation is given the Telegraph story

The findings show that blood pressure and diabetes appeared to take over as one of the main influences on having a stroke at around the age of 75.

That is, the alcohol effect was mostly in middle-aged people, where the actual stroke risk is lower. This was the main finding of the research, in fact. It still wouldn’t entirely explain the lack of difference in alcohol consumption, but there’s also probably a contribution from the statistical model they used and the way it handles people who die of something other than a stroke, and from lower risk in light drinkers than in non-drinkers.

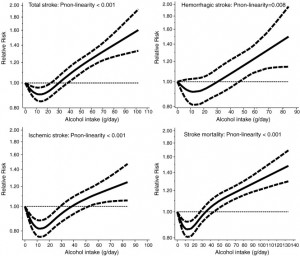

The other question to ask, always, is what other research there is. Here’s a graph from a meta-analysis combining 27 alcohol and stroke studies published last year (click to embiggen). It also shows an increase, but not as dramatic as the new study.

Since the new study wasn’t particularly well suited to looking at the effect of heavier drinking (it would have been better for looking at non-drinkers vs light drinkers), there isn’t much case for preferring the single new study estimate over the combined estimate. According to this estimate, at 2 drinks/day there isn’t convincing evidence of increased risk. Above 3 drinks/day there is, and it goes up rapidly after that. Another meta-analysis in 2010 found broadly similar results, as did one in 2003 in the prestigious journal JAMA.

So, not really debunked, but not quite as bad as it sounds.

Thomas Lumley (@tslumley) is Professor of Biostatistics at the University of Auckland. His research interests include semiparametric models, survey sampling, statistical computing, foundations of statistics, and whatever methodological problems his medical collaborators come up with. He also blogs at Biased and Inefficient See all posts by Thomas Lumley »

One of the thorny problems that comes with studies of alcohol exposure are the people who don’t consume alcohol at all. This is an interesting mixture of abstainers, ex-alcoholics, and people who are currently in poor health.

A history of exposure is very helpful, but is also fairly difficult to obtain.

I can’t access the article here, so please consider this a general comment.

9 years ago

Yes, that is an important general problem. It’s not a problem for the effects of heavier drinking this new study, because the comparison group was people who did drink regularly, but less than 0.5 drinks per day. The same is true for most of the studies in the meta-analysis.

Where the abstainer problem will have some impact is on the apparent protective effect of low-level alcohol consumption. It’s not as bad as one might expect, though. Firstly, many of the studies measure alcohol use a long time before the health events (in this new study,up to 43 years before), so poor health or recent ex-alcoholism won’t have an effect. Secondly, it’s fairly common to ask people if they have ever consumed substantially more alcohol than they do now. Not everyone will be honest, but many will.

9 years ago