Out of warranty?

A new medical study (reported here and here) used MRI to look at the shoulders of a reasonable representative sample of 602 people over 40 in Finland. Rotator cuff abnormalities of varying apparent severity were seen in 595 of the people: that’s 99% to two digits accuracy. Of the 602 people, 18% reported shoulder pain and the other 82% claimed their shoulders were ok (apart from being over 40).

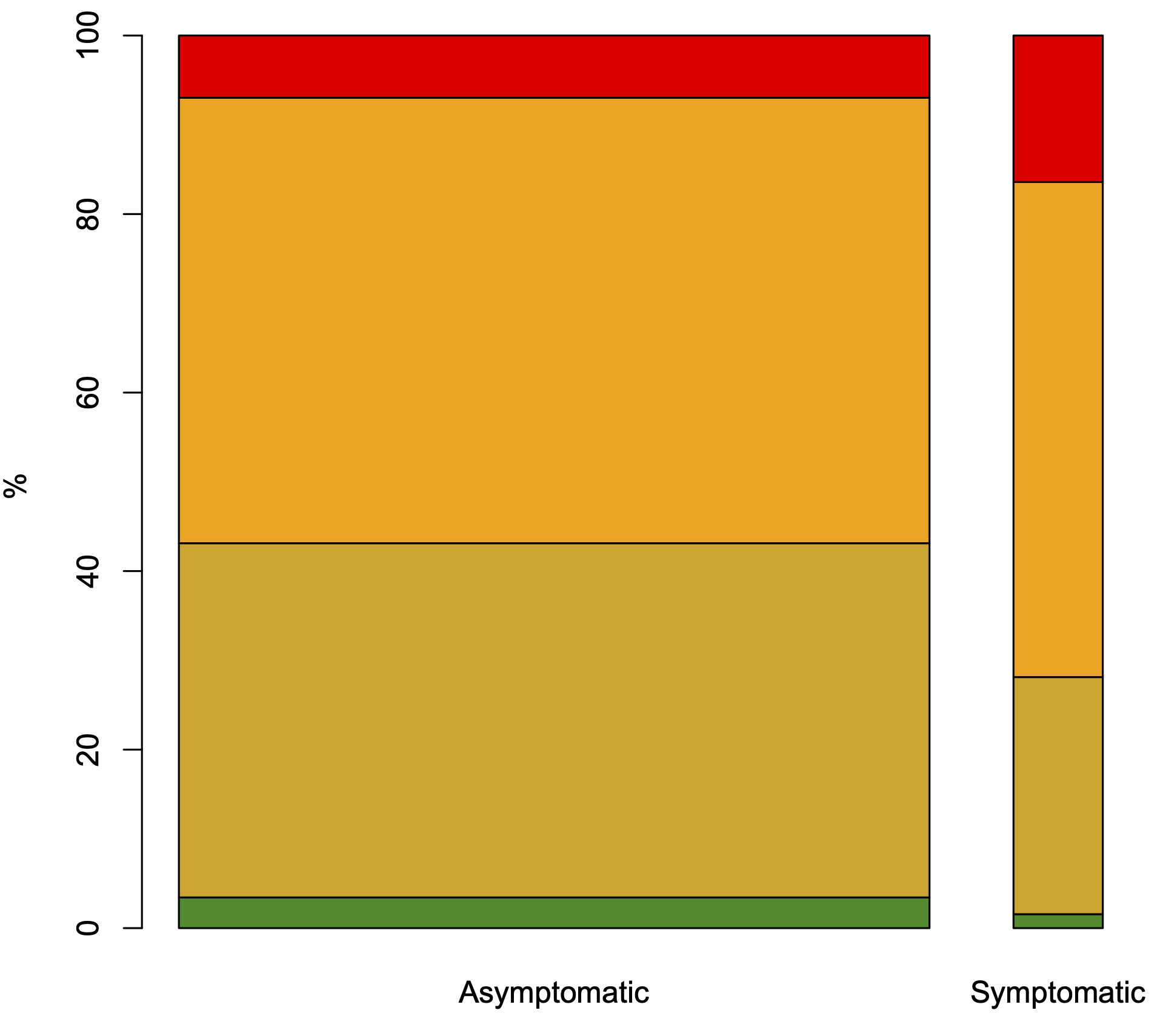

There wasn’t much difference between the people who noticed their shoulders hurting and the ones who didn’t: here’s a graph comparing asymptomatic and symptomatic shoulders, so someone with one bad shoulder and one over-40-but-otherwise-good shoulder is in both groups. The green at the bottom is “no abnormality”, then we progress through “tendinopathy”, “partial-thickness tear”,”full-thickness tear”.

You can see the abnormalities are a bit more severe in the symptomatic group, but not enough to make a useful diagnostic test. On top of that, the researchers showed that the difference largely goes away when you adjust for things a doctor would have measured before doing the MRI, so the MRI really isn’t providing much useful information.

We’ve seen this before. New medical-imaging tech gets used first on people who look like they need it. A lot of people with back pain were given CT scans. These showed that people with back pain had weird misshapen spines, and often led to referrals for surgery. It was much later that people not reporting significant back pain had their backs scanned — and they, too, often had weird misshapen spines. Spines are just badly designed and implemented.

Medical imaging can be immensely valuable: simple X-rays, CT scans, MRI, PET, and so on. One of Marie Curie’s many claims to fame was designing, deploying, and driving mobile X-ray units in the Battle of the Marne. But with each shiny new technology for subtler and more precise imaging there’s an increasing need for control data. Marie Curie could see a piece of lead in a soldier’s heart and be confident that it wasn’t normal. The problems we’re looking for in shoulders and spines are more complicated and comparisons are important.

Thomas Lumley (@tslumley) is Professor of Biostatistics at the University of Auckland. His research interests include semiparametric models, survey sampling, statistical computing, foundations of statistics, and whatever methodological problems his medical collaborators come up with. He also blogs at Biased and Inefficient See all posts by Thomas Lumley »