Thanksgiving

It’s well into Thanksgiving Day in the US now, and that’s a nice tradition to export. So, today, I’m thankful for geophysics.

In the Late Bronze Age, it made perfect sense that earthquakes were caused by God or gods getting upset. That, on a larger scale, is how people often behave, and whether we are made in God’s image or he in ours, you’d expect some similarities. And when an earthquake destroys a city, well, whether you think God is more offended by homosexuality or homelessness, by not giving enough to the temple or not giving enough to the poor, there’s going to be something in any major city to piss him off.

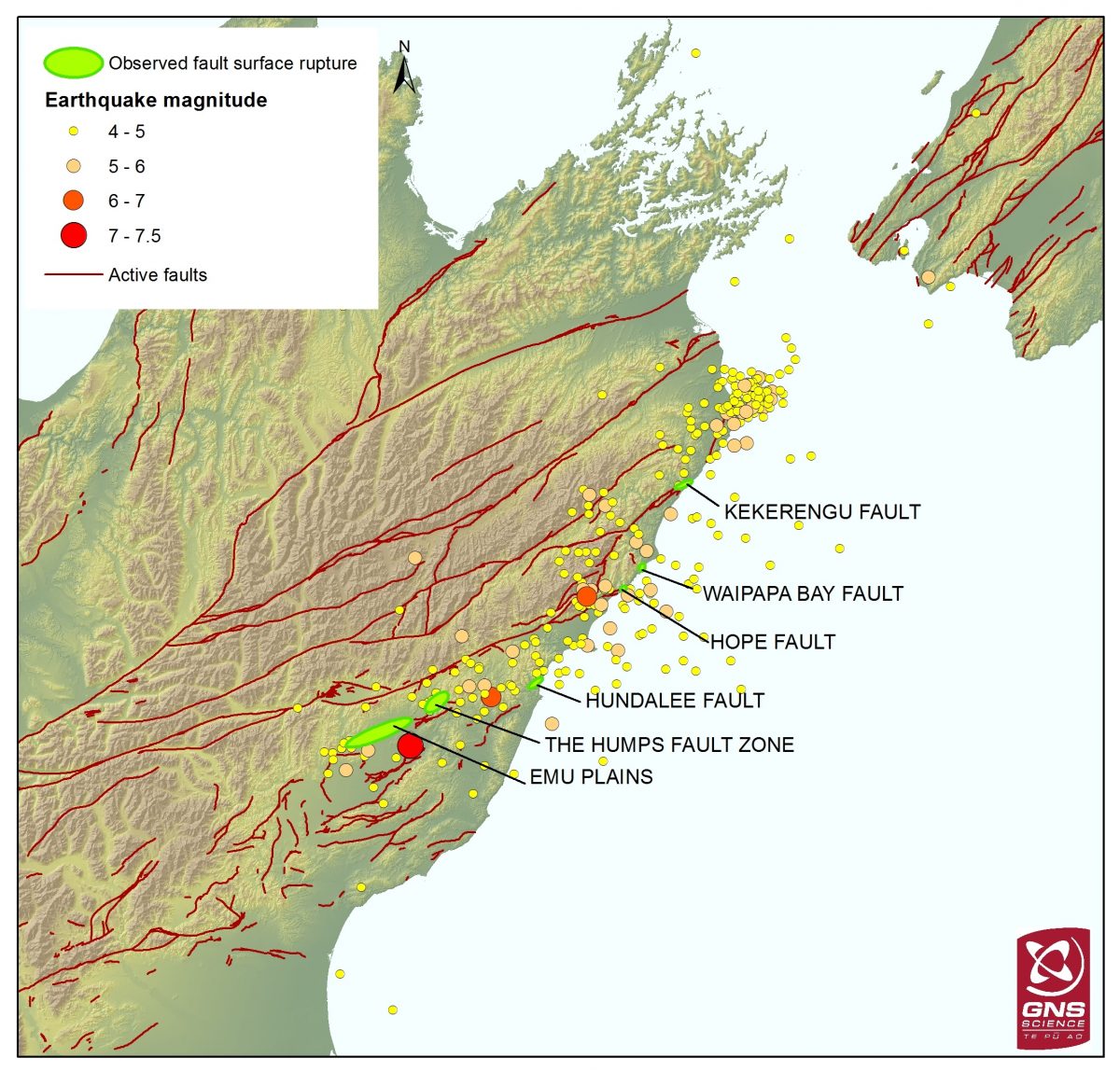

Now we have maps like this one from GNS Science:

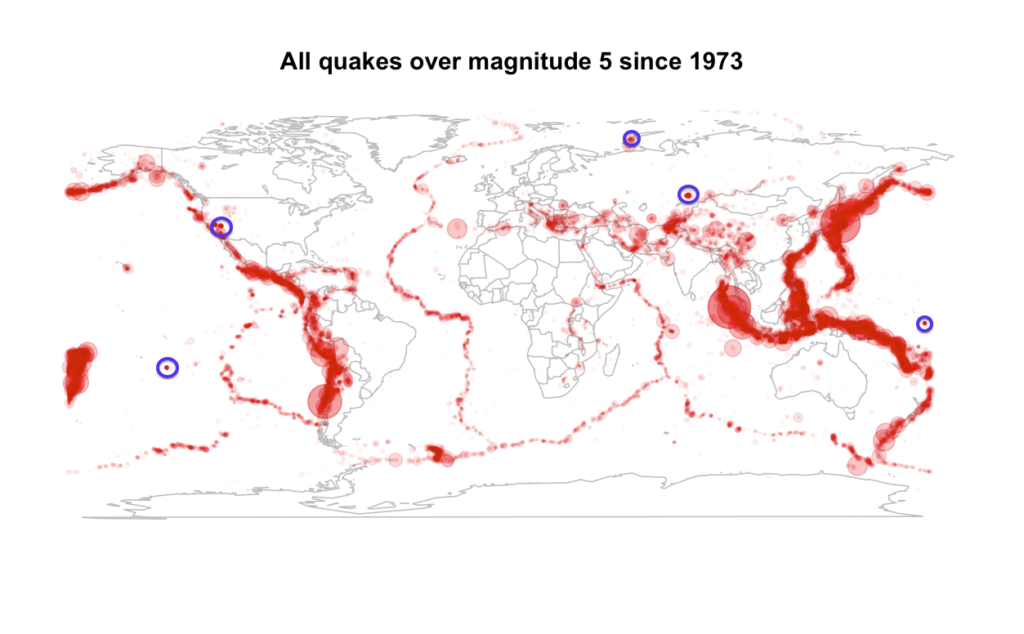

and this one, which I made for a very early StatsChat post, showing all sufficiently-large earthquakes from 1973 to mid-2011.

Working from travellers’ tales in the Middle East it would be impossible to see the patterns, but technologies including GPS, helicopters, the internet, and a worldwide network of seismometers makes them much clearer. Earthquakes mostly happen along a small set of lines, and scientists can measure the strains in the rock around those lines that lead to the earth rupturing. The global pattern, together with a vast network of other evidence, fits an explanation where whole continents are pushed around on the Earth by convection deep inside, bumping and grinding as they collide. It doesn’t fit an explanation based on human behaviour being different in different places — even though that might seem a less grandiose explanation before we got the data.

There’s a lot we don’t know about earthquakes, but we understand them well enough to make high-risk/low-risk predictions, to describe the patterns of aftershocks, to do tsunami warnings (on a good day), and to buy and sell earthquake insurance. We don’t know exactly why one building is destroyed and another is spared, but there aren’t any mysteries about it: it’s the sort of thing we could work out given time and money.

Science isn’t a pure good; there are many things we can go with more knowledge of the world, and the blue circles on the world map above show some seismic events that are the result of human action. But even they have become less frequent.

And now that God has gotten out of the natural-disaster business, many people in this country don’t believe in him, and those that do still believe mostly (with sad exceptions) have a higher opinion of him than their ancestors did.

Thomas Lumley (@tslumley) is Professor of Biostatistics at the University of Auckland. His research interests include semiparametric models, survey sampling, statistical computing, foundations of statistics, and whatever methodological problems his medical collaborators come up with. He also blogs at Biased and Inefficient See all posts by Thomas Lumley »

When the very first basic weather forecasts were made and released to the public some people said you cant do that as it would be presuming to reading Gods mind about the future.

7 years ago

There’s an interesting xkcd about earthquakes

https://xkcd.com/723/

with relevant roll-over text and

interesting commentary

https://blog.xkcd.com/2011/08/24/earthquakes/

7 years ago

I find this blog very interesting and I appreciate the witty comments very much. I have to say that it is not the case now. Although there is little question about blaming people who want to find correlation (and causality!) between natural disasters and “homosexuality or homelessness”, I don’t find any need for additional extrapolations leading to the conclusion that God can be “pissed off”.

7 years ago