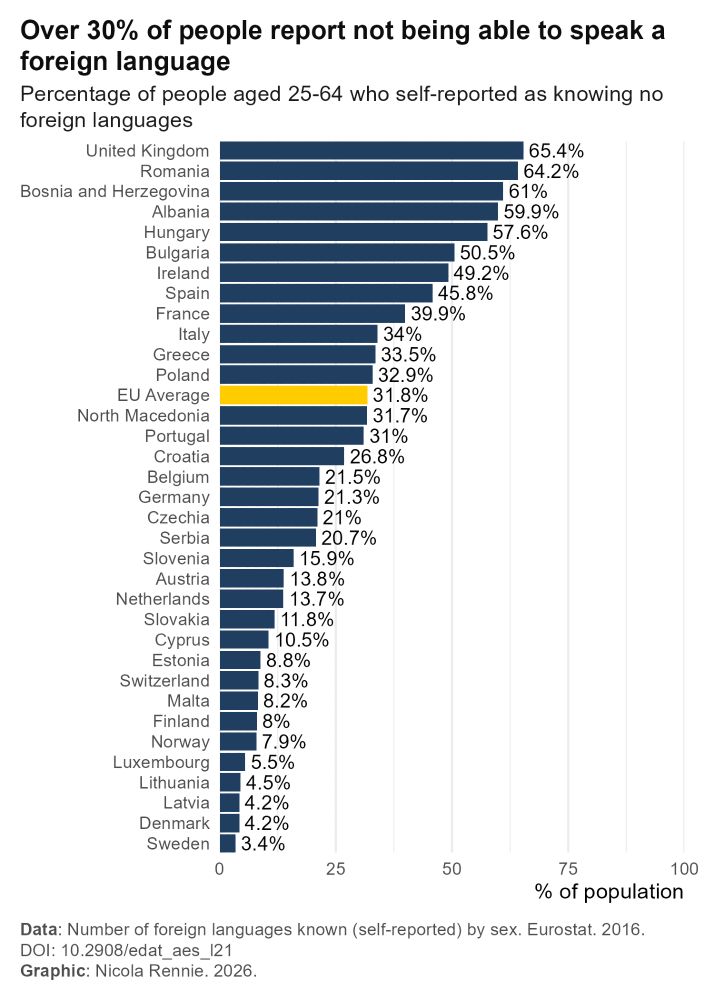

From Nicola Rennie on Bluesky, a bad graph found on LinkedIn:

and a correct version of the same graph

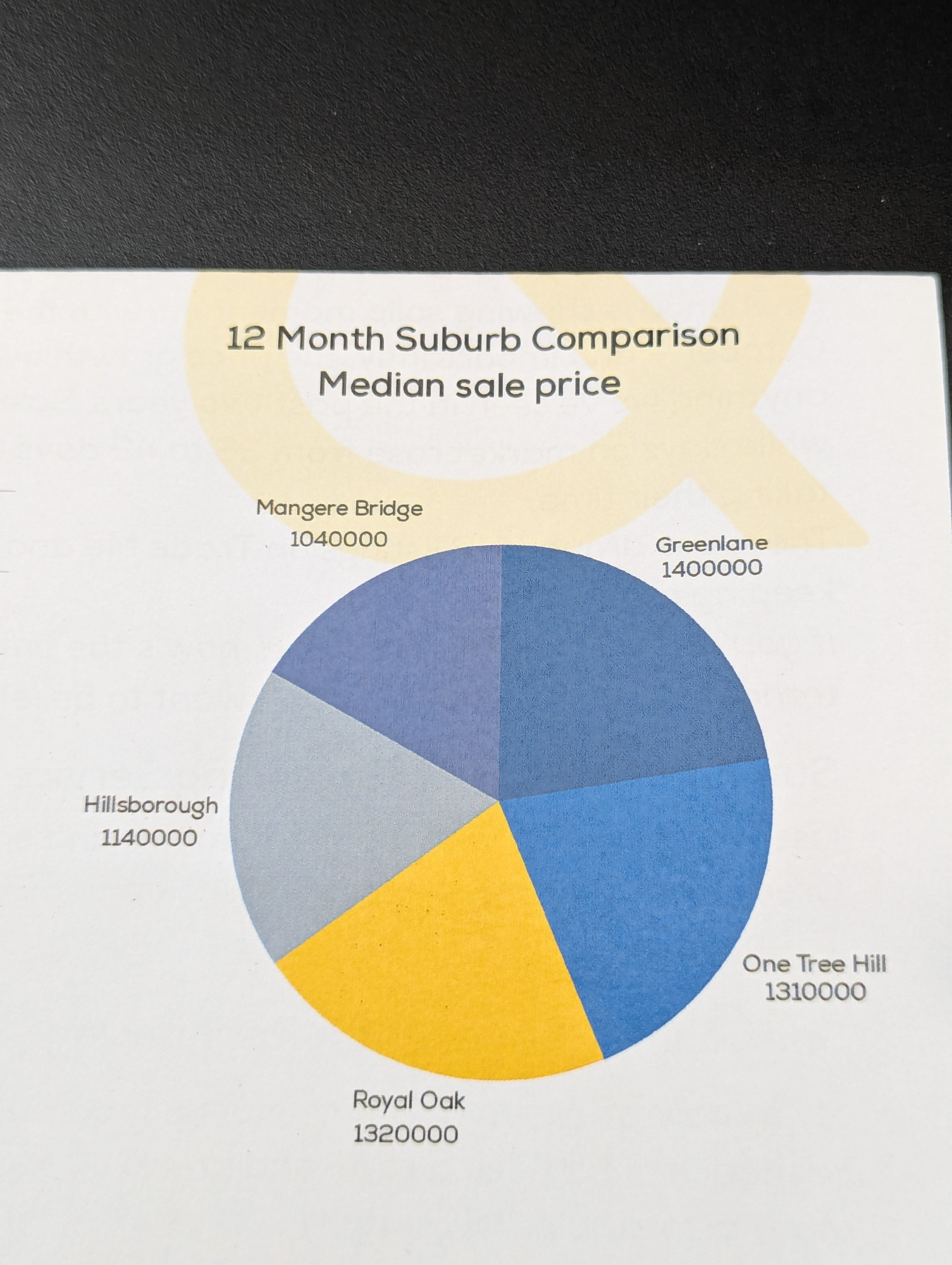

The bad version is probably from generative AI — as Nicola says, it is bad in ways that would take substantial effort to achieve in commonly-used software, ranging from the weird bar alignment to the incorrect lengths to the incoherent choice of colours to the Slovenioid flag to the spelling of Belgıun. It’s also a bit vague about the data source, but that’s easy to achieve by hand.

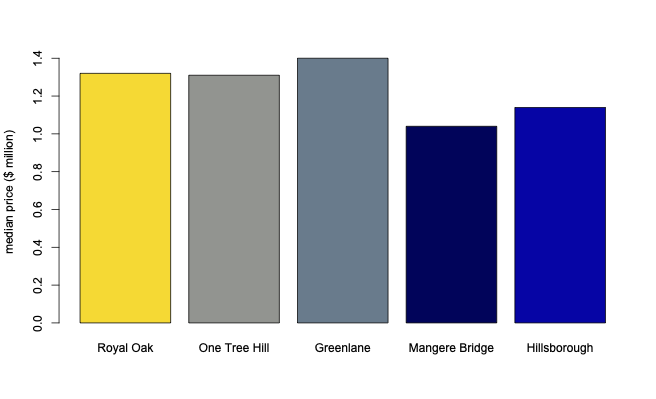

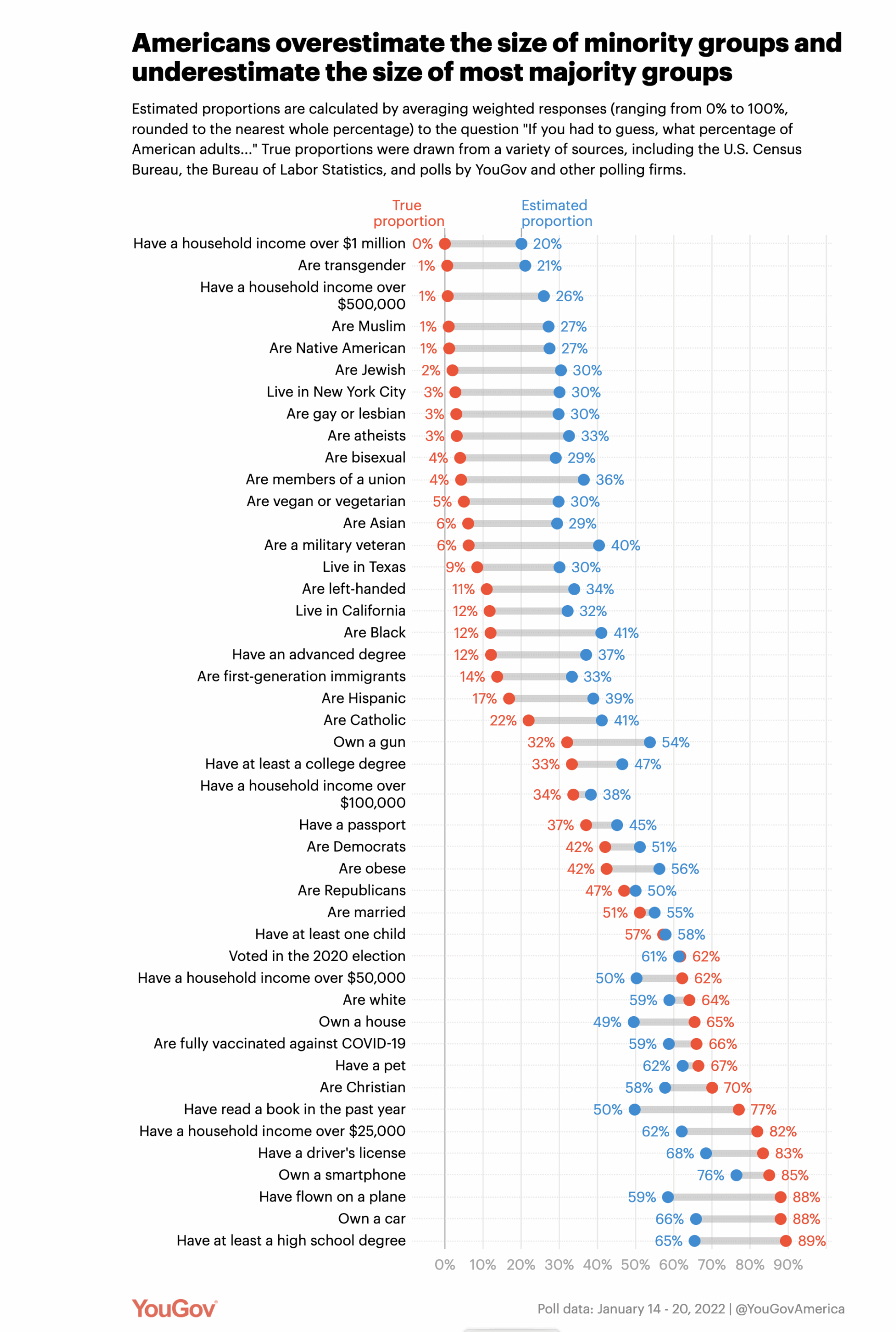

The corrected version is a lot better, but brings out that this is actually hard to interpret. What’s a “foreign” language? If you’re Welsh or Irish, can English count? Can Spanish count for the Basques? Less politically, if you’re Czech and you speak Slovak, is that a foreign language? Is it still a foreign language if you learned it before 1992? If you grew up in Ghent, speaking Flemish and French, and learned English at school then you know one foreign language, but if you move to London do you suddenly know two foreign languages?

You might say “language that is not an official language of where you live”, which is less ambiguous but does require identifying all the official languages of where you live. These are typically well-known within any the country or region (though there are people who profess to be confused about whether English is an official language of New Zealand), but they can be hard to determine by database search.

Kieran Healy, of Duke, gave an excellent talk last year about “Trustworthy Data Visualisation“: having graphs you can trust is not just about reproducibility in a simple sense, but about the systems that allow you to trust what you see: The important thing is not to lose sight of the collective, cooperative character of the whole enterprise.

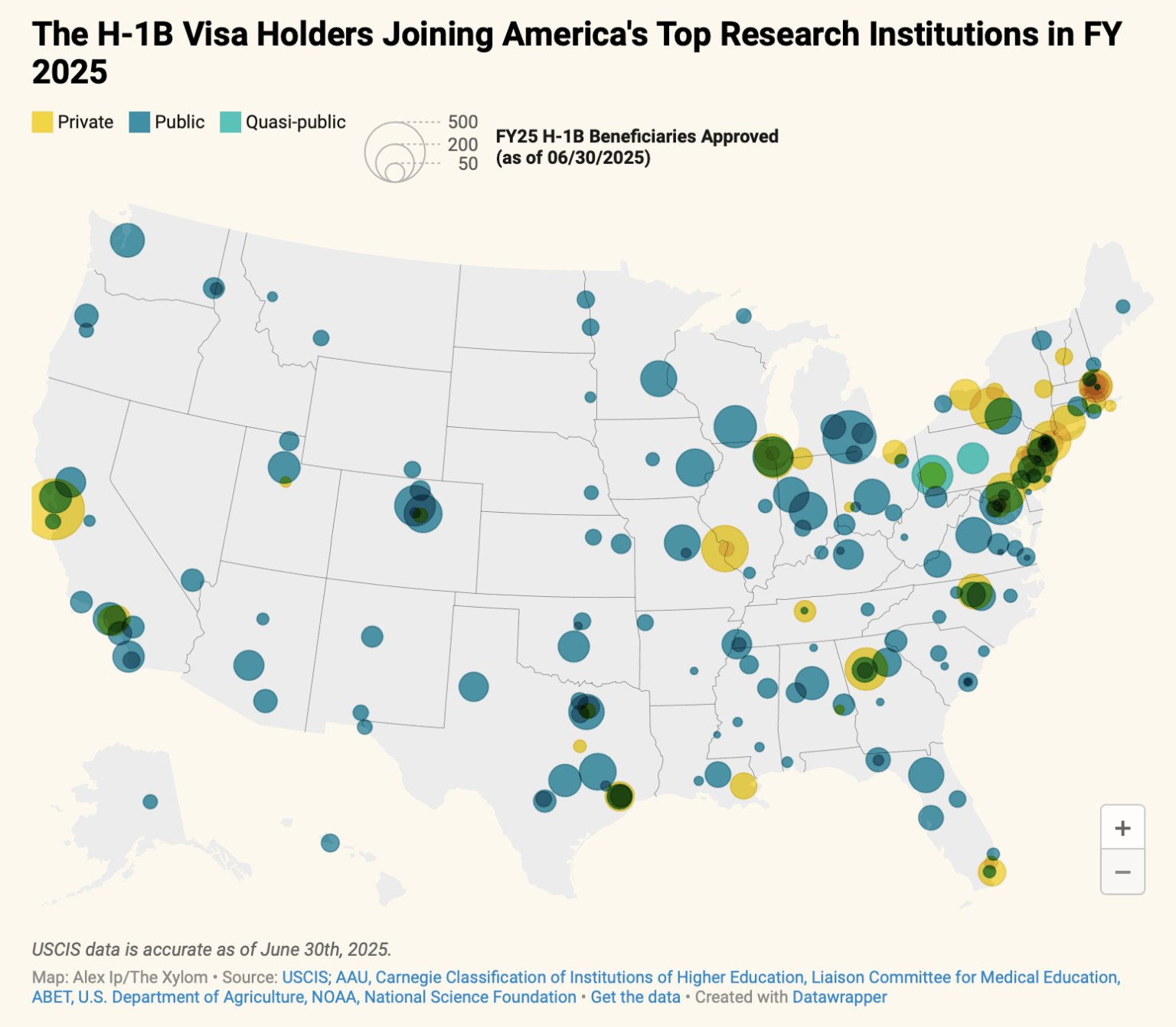

Cross-national comparisons require that someone in each country has collected data, that the data answer the question you are interested in, that the biases and edge cases are either unimportant or the same across the countries, that the data have been accumulated, and that someone has drawn a graph. In the past, all these steps were done by accountable people or organisations who were (or perhaps weren’t) honestly trying to provide good information. All these steps became more accessible over the past few decades, but we may be about to lose it all again.

You might well have good and sufficient reasons to trust your vibe graphics for your purposes. It’s hard to see how other people can have good and sufficient reasons to trust them, though.