Obesity and Covid deaths

Q: Did you see 90% of Covid deaths are due to obesity?

A: No

Q: It’s on Newshub: “90 percent or 2.2 million of the 2.5 million deaths from the pandemic disease so far were in countries with high levels of obesity.”

A: So, if that’s true, what countries are we talking about?

Q: With high levels of obesity? Australia, New Zealand, some of the Pacific Island nations, USA, UK,…

A: And what don’t those countries have in common?

Q: Lots of Covid deaths, I suppose. But Australia and NZ and the Pacific Island countries didn’t have many deaths just because they didn’t have many cases. They don’t tell you anything about the risk

A: Neither does the ‘report’, which says, according to Newshub, “the majority of global COVID-19 deaths have been in countries where many people are obese, with coronavirus fatality rates 10 times higher in nations where at least 50 percent of adults are overweight”

Q: That sounds bad, though? Ten times higher is a lot!

A: How much do you think being overweight increases the risk of death?

Q: Well, if 50% overweight means ten times the risk, maybe a factor of twenty?

A: Yeah nah. Less than double, according to that very same report. (PDF, p13)

Q: So where do they get such a strong association?

A: Well, what are the main risk factors for dying of Covid?

Q: Um. Age?

A: And?

Q: Heart disease? Diabetes?

A:

Q:

A:

Q: Having Covid?

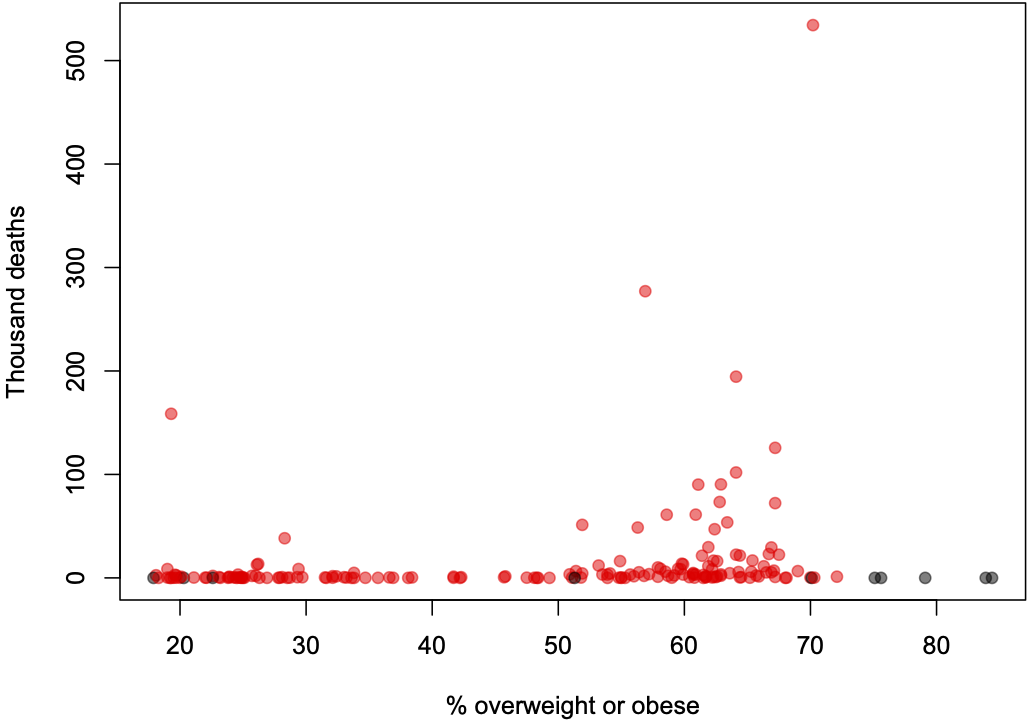

A: Exactly. So we’d need to look at the proportion of infected people dying (the case fatality rate), not the total number of deaths, and we’d ideally want to compare countries with similar age profiles. Instead, Newshub shows us a graph of deaths, basically like this

Q: Why are some of the dots black?

A: They are countries that were missing from the Johns Hopkins Covid data, and so were missing from the original graph, mostly small nations like Samoa and Tonga and Timor-Leste with very few cases

Q: And what’s the dot on the left that isn’t in the graph on Newshub?

A: Afghanistan. I don’t know why it’s not there.

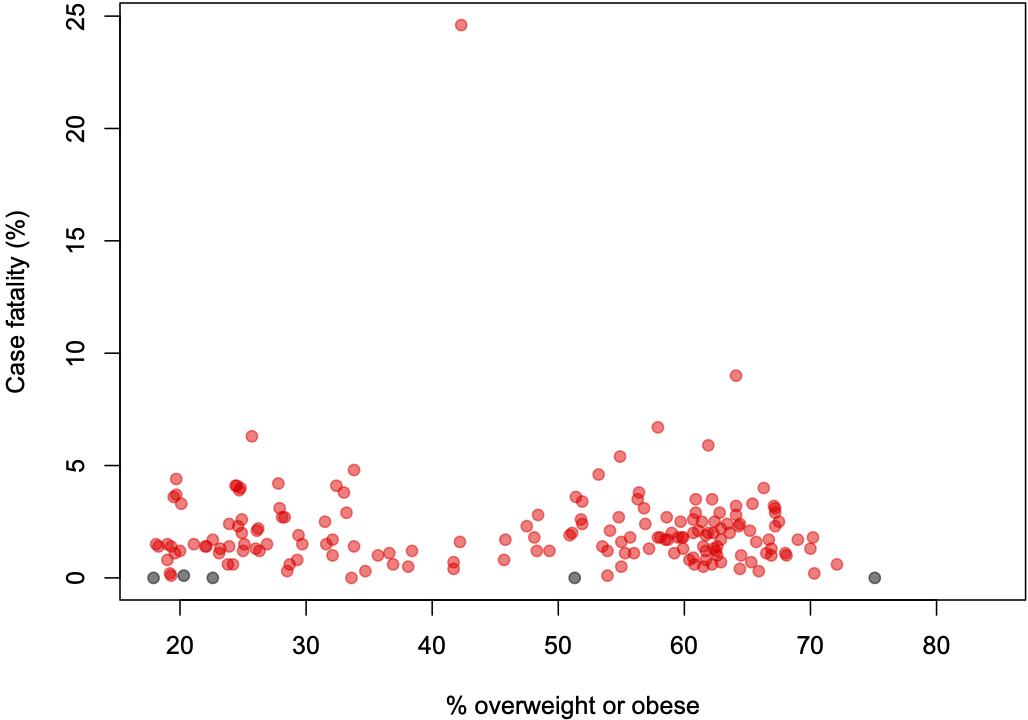

Q: So what about for risk of dying if you get Covid?

A: Here’s what it looks like for case fatality rate

Q: That’s…surprisingly unimpressive. Well, except for that one country…

A: Yemen

Q: Things they don’t need right now, number #1

A: Too true.

Q: So the massive correlation?

A: Well, overweight is common in the USA, the UK, Brazil, and various other large countries that have handled the pandemic badly. While I suppose you could argue that handling the pandemic well should go with handling other public health issues well, the empirical evidence would not really be in your favour on that one. You could also listen to a slightly different approach to the data from David Spiegelhalter and Tim Harford on BBC’s “More or Less”