This time we might be number one

So, Radio NZ has a story based on a commentary at YaleGlobal on homelessness.

The point of the YaleGlobal piece is that homelessness is increasing as the world gets more urbanised, and that it’s really hard to measure because people define it differently and because some countries don’t want it measured accurately. Overall

Based on national reports, it’s estimated that no less than 150 million people, or about 2 percent of the world’s population, are homeless. However, about 1.6 billion, more than 20 percent of the world’s population, may lack adequate housing.

There’s obviously a lot of room for variation in definitions.

This report isn’t Yale research, really. It’s based on OECD figures, which are reported by governments: the OECD HC3-1 indicator (PDF). The number for New Zealand is 41705, which we’ve seen last year in the NZ media. It comes from the 2013 census, and was estimated by researchers at Otago. The NZ homelessness number is high for at least three reasons. First, NZ uses a very broad definition of homelessness. Second, we’re pretty good at honest data collection. And, third, we’ve got a serious homelessness problem (and have had for a while).

The Government is right to say that the international figures aren’t all comparable. Some countries only count people who are sleeping rough. Others include people in shelters or emergency accomodation. We include a lot more. The Herald story from last year quotes an Otago researcher, Kate Amore

“If the homeless population were a hundred people, 70 are staying with extended family or friends in severely crowded houses, 20 are in a motel, boarding house or camping ground, and 10 are living on the street, in cars, or in other improvised dwellings.”

From that tally, a few countries don’t even count all of the 10; some don’t count all of the 20; many don’t count the 70 — and some aren’t very good at counting.

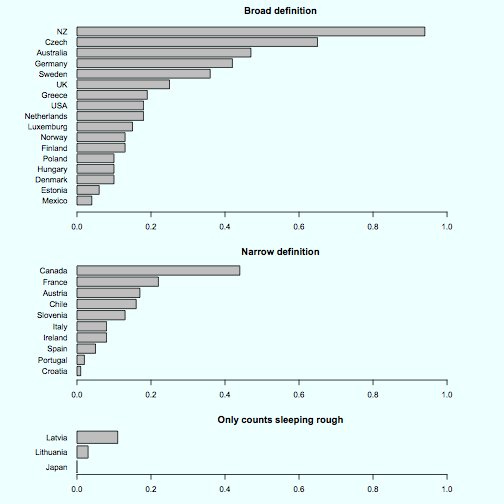

Here’s a set of charts I made based on a crude classification of definitions from the OECD HC3-1 report. The numbers on the axis are in % of the population.

Even within the top panel, NZ, the Czech Republic, and Australia have the broadest definitions. The HC3-1 report says

Australia, the Czech Republic and New Zealand report a relatively large incidence of homelessness, and this is partly explained by the fact that these countries adopt a broad definition of homelessness. In Australia people are considered as homeless if they have “no other options to acquire safe and secure housing are without shelter, in temporary accommodation, sharing accommodation with a household or living in uninhabitable housing”. In the Czech Republic the term homeless covers “persons sleeping rough (roofless), people who are not able to procure any dwelling and hence live in accommodation for the homeless, and people living in insecure accommodation and people staying in conditions which do not fulfil the minimum standards of living […]”. In New Zealand homelessness is defined as “living situations where people with no other options to acquire safe and secure housing: are without shelter, in temporary accommodation, sharing accommodation with a household or living in uninhabitable housing.”

I think the New Zealand definition is a good one for measuring the housing deprivation problem, but it’s not good for international comparisons.

On the other hand, the comparison to Australia is pretty fair, and there’s at least no evidence that anywhere else has higher rates. To some extent we have an apples vs oranges comparison, but that doesn’t stop us concluding it’s a bad apple.

Thomas Lumley (@tslumley) is Professor of Biostatistics at the University of Auckland. His research interests include semiparametric models, survey sampling, statistical computing, foundations of statistics, and whatever methodological problems his medical collaborators come up with. He also blogs at Biased and Inefficient See all posts by Thomas Lumley »

When I think of homeless I think of sleeping rough. The people who slip through the social safety net, not those in emergency housing.

When I looked up at the otago paper, they quickly started talking about severe housing deprivation rather than homelessness in the tables

7 years ago

When the only option for emergency housing is a motel room where the user is charged extortionate rates with no ability to negotiate then it’s not much of a safety net.

7 years ago

I would have assumed that all the ‘no fixed address’ forms of homelessness were counted. But it’s clear from the international comparisons that expectations vary a lot.

On the other hand, while we can just have different expectations, I think it’s unreasonable for the Minister to object to an official NZ definition updated in 2015.

7 years ago

Having been NFA in my mid 20s, the difference between my experience and street-based homelessness was massive. But both are terrible. Getting out of either scenario is a lot harder than most people understand.

I’m a bit out of the loop there (after nearly 5 years living in NZ), but in Canada municipal data more often seemed to focus on NFA versus homeless (“sleeping rough” if ever there was a wonky euphemism), though the aggregate of the two figures was discussed at times. The social support requirements of the two groupings are very different: often NFA have access to non-governmental peer or familial support, whereas homeless don’t (or no longer do). There is a raft of housing provision targetting the “hard to house” as well: people with severe mental illness or addictions or both. Expensive to run; less expensive that letting them become homeless and an even greater cost to the public because of health outcomes. Ostensibly.

Regardless, we need more homes, particularly social housing.

7 years ago

Yes, these are all real issues — and that’s part of why the YaleGlobal story talked about international comparisons being hard. It’s a bit like measuring unemployment, except that the most serious cases are the hardest to measure, when they’re the easiest to measure for unemployment.

I’m still in favour of the headline national indicator being a broad one. In contrast to unemployment, I don’t think there’s any likely intervention that will reduce homelessness by the NZ definition but increase it on a narrower definition.

7 years ago

If they’re capturing decent data then they’d be able to calculate a value to match each international definition. They do something like this for money supply.

In fact, it goes up to M7 so there are seven different definitions for quantity of money.

In this day and age of big data, machine learning and the Internet of Everything to say that it’s too hard to measure something or data is not comparable is unacceptable.

7 years ago

They could — as they do with unemployment and (as you say) money — but the NZ definition is based on an international standard that they probably hope other people will also implement ( see here).

On the other hand, it definitely would be helpful to known which definition corresponds to the roughly 0.1% number the Minister is pushing.

7 years ago

Still surprises me that the US, using a broad definition, comes in so low. The incidence of on-the-street homelessness is so pervasive there compared to here. Any thoughts?

7 years ago

Yes, that’s a bit surprising. Part of it is that the US is much less urbanised than I tend to remember, and that the non-coastal parts have relatively cheap housing.

7 years ago

It does seem odd that the Canada on the narrow definition beats the USA on the broad definition. Maybe the USA isn’t trying too hard to find them so that they can count them.

Here it says that 6% of the USA population lives in trailer parks which would be the (rough?) equivalent to NZ’s camp grounds.

https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2015/may/03/owning-trailer-parks-mobile-home-university-investment

7 years ago