Sweet as?

There’s been a scary news story about an artificial sweetener that previously looked remarkably inoffensive, erythritol. It’s produced by fermentation of various plant material, and it comes in ‘organic’ as well as normal versions; it’s got similar taste and feel to sugar, and you can even use it for baking. So when someone reports that it increases the risk of heart attack by a lot, you’d hope they had investigated thoroughly.

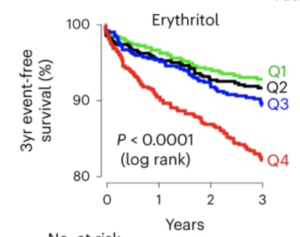

The researchers didn’t particularly have it in for erythritol; they were looking at blood components to see if anything predicted heart attack by a useful amount, and found a dramatic correlation with the amount of erythritol in the blood — and I mean dramatic. Here’s the chart showing the percentage of people who didn’t have a heart attack over the three years after their blood measurement, divided into four equal groups based on erythritol in the blood:

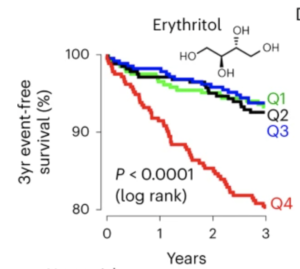

It’s not quite as bad as it first looks — the y-axis only goes down to 80% — but it still suggests more than half of heart attacks are due to erythritol, making it almost as bad as smoking. And also that there’s a magic threshold between safe and dangerous doses. This is … hard to believe? Now, this was the group where they discovered the correlation, so you’d expect over-estimation. Not being completely irresponsible, they did check in other groups of people. Here’s a separate US group

It’s not quite as dramatic, but we’re still looking at a doubling of risk in the highest group and no real difference between the other three. And we’re still looking at nearly half of heart attacks being due to this obscure artificial sweetener.

So it is credible?

One question to ask is whether there’s a mechanism for it to be dangerous — this isn’t a definitive criterion, because there’s a lot we don’t know, but it’s useful. The researchers say that erythritol makes platelets more likely to clump together, triggering clots, which is a thing that can happen and would increase heart attack risk — that’s why aspirin, which disables platelets, has been recommended to prevent heart attacks.

Another question to ask is whether the high erythritol group got it from eating the most erythritol. If they aren’t, this isn’t going to give useful dietary advice. The compound is made in the body to some extent, and it’s excreted via the kidneys. Could people at higher risk of heart attack be making more internally or excreting it less effectively? The natural step here would be to feed healthy people some erythritol and see what happens to their platelets. That study is apparently underway, though it’s small and has no control group.

You might also ask if there has been a dramatic increase in heart attacks over the time that erythritol has become more popular in foods? There hasn’t been, though a moderate increase might have been masked by all the other factors causing decreases in risk.

I would be surprised if the risk turns out to really be this big, though it’s entirely possible that there’s some risk. At least the platelet study should be reasonably informative, and it’s a pity it wasn’t done before the publicity.

Thomas Lumley (@tslumley) is Professor of Biostatistics at the University of Auckland. His research interests include semiparametric models, survey sampling, statistical computing, foundations of statistics, and whatever methodological problems his medical collaborators come up with. He also blogs at Biased and Inefficient See all posts by Thomas Lumley »

This is a bit of a problem. I have seen literature elsewhere suggesting that the sugar replacements are not necessarily proven to be safer than sugar consumption. That busts a major potential public health intervention, unless we can just get people off “sweet stuff”. You know, instead of a sugary drink being replaced by one with an artificial sweetener, will it have to be just water or water with some kind of flavouring?

1 year ago

They haven’t, because it’s almost impossible to collect the data. Basic safety is feasible, but long-term comparisons with sugar really aren’t

Another issue here is that `artificial sweeteners` isn’t a meaningful biological category — cyclamate, saccharin, erythritol, aspartame, lead acetate, sucralose, acesulfame, stevia, sorbitol etc. The only thing they have in common is stimulating the sweet taste receptor

1 year ago

My first question would have been: are there any confounders? It seems obvious that people who eat erithrol have a different behavioral pattern from people who don’t, and the reason may be due to, for example, obesity, or other clear risk factors that the patients are aware of (smoking? history of heart disease? drinking?).

My nasty suspicion is that the story might boil down to “people who consume erithrol because they are at risk of heart attack are more likely to have a heart attack”, which is not unexpected.

It appears that the researchers controlled for some of these factors (BMI, blood pressure, diabetes, sex). And indeed, at least in the validation cohorts, the effect was strongly diminished when correcting for these factors (even though they did not correct for BMI in the European cohort).

However, I would argue that this is the most problematic point of the analysis and would not rely on a single method. Instead, I would try very hard to figure out how I could make the effect disappear using the clinical data at hand, and make sure that the effect of confounders really is subtracted from the data.

OTOH the experiments with platelets are convincing. Maybe there is an interaction between other risk factors and erithrol? So the effect of erithrol manifests more profoundly in those already at risk.

1 year ago