Up or down

The Herald (from the Daily Mail, sadly) has a headline “Baby girls exposed to stress have great risk of teen anxiety”. “How great?”, you ask. They don’t say.

We do learn:

Teenage girls are more likely to struggle with anxiety and depression if they’re exposed to stress as babies, a study has found.

If you go to look at either the abstract, or the more comprehensible explanation in Nature News, you find that this isn’t quite right

The study showed that 18-year-old girls who had had high cortisol levels at age 4 have weak connectivity between the amygdala, a deep nub of the brain known for processing fear and emotions, and the ventromedial prefrontal cortex, an outer region involved in curbing the amygdala’s stress response.

But without taking cortisol into account, early stress, in itself, is not significantly correlated with the differences in brain activity seen at age 18…

The study also found that girls who have higher scores on anxiety tests have weaker synchrony between these two regions than do girls with lower scores. Intriguingly, the opposite pattern was found for depressive symptoms: higher depression scores correlate with stronger connectivity.

Or, in the original Greek

For females, adolescent amygdala-vmPFC functional connectivity was inversely correlated with concurrent anxiety symptoms but positively associated with depressive symptoms,

Nothing about the opposite findings for anxiety and depression made it into the story. If you go on to read the full article, you also find that while they measured early life stress and they measured symptoms of adolescent anxiety and depression, they don’t report on the associations between them. The analysis is about how the other variables related to the brain wave patterns. At least, for a change, the gender differences in the story are supported by the research.

The research is actually quite interesting and potentially useful, and the correlations between cortisol levels and brain waves are respectably strong. Much stronger, for example, than the link between the results and the headline and lead in the story.

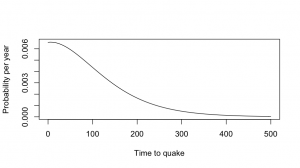

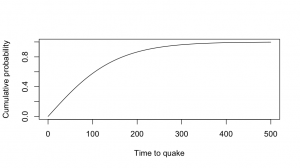

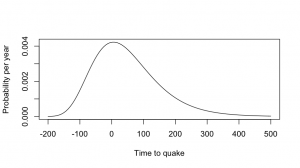

This is a simple and reasonable model for time intervals, and it also has the virtue of giving the same answers that the researchers gave to the press. Using the estimates of mean and variation in the paper, the distribution of times to the next big quake looks like the first graph. The quake is relatively predictable, but “relatively” in this sense means “give or take a century”.

This is a simple and reasonable model for time intervals, and it also has the virtue of giving the same answers that the researchers gave to the press. Using the estimates of mean and variation in the paper, the distribution of times to the next big quake looks like the first graph. The quake is relatively predictable, but “relatively” in this sense means “give or take a century”.