Opinions about immigrants

Ipsos MORI do a nice set of surveys about public misperceptions: ask a sample of people for their estimate of a number and compare it to the actual value.

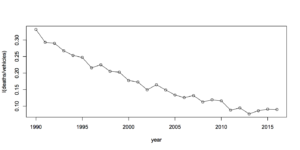

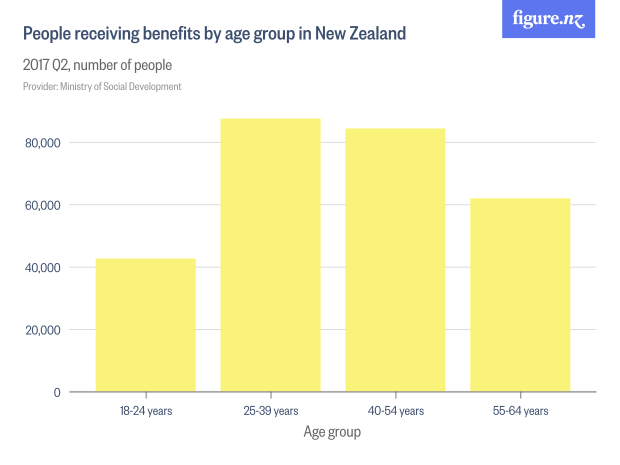

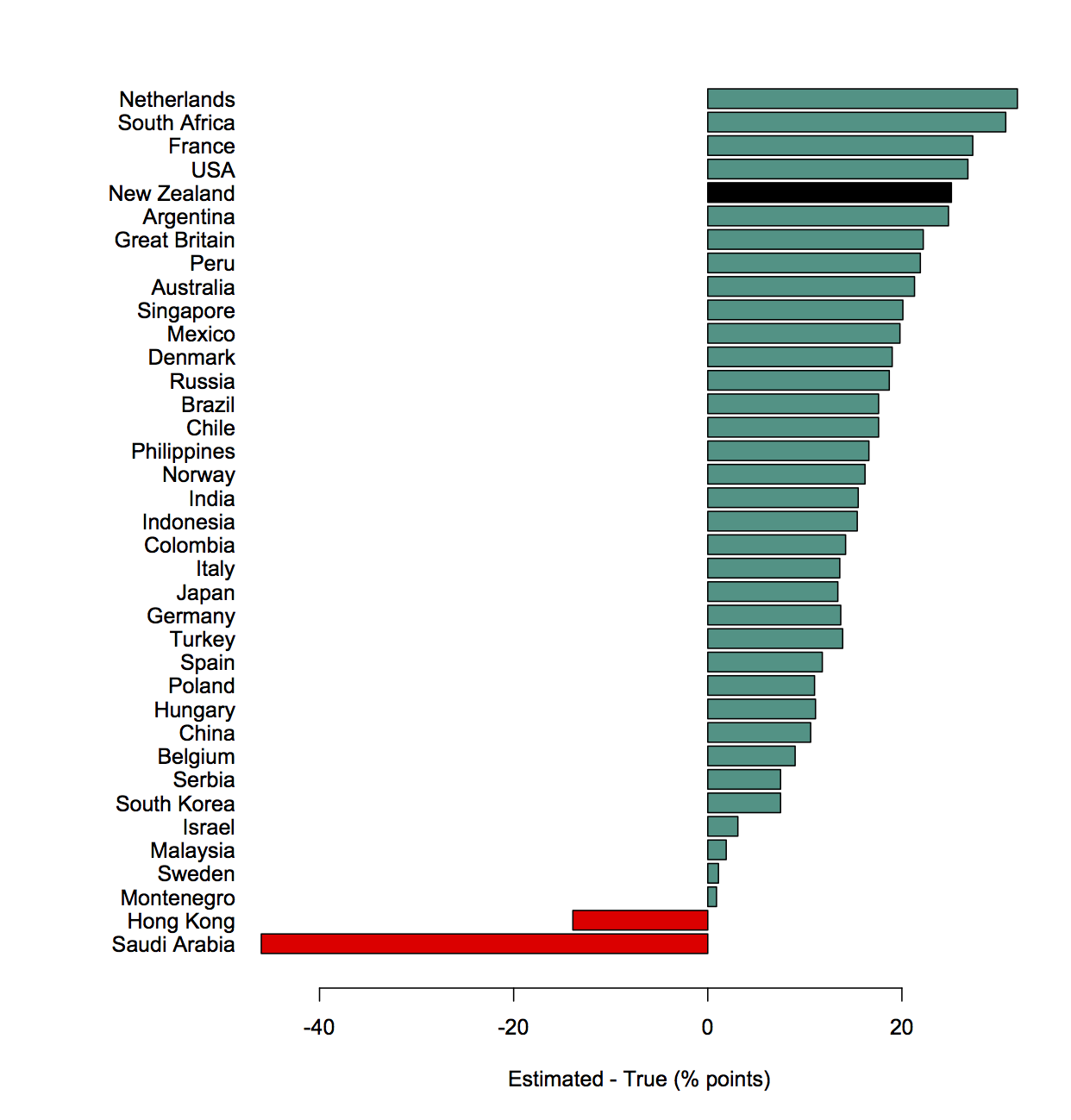

The newest set includes a question about the proportion of the prison population than are immigrants. Here’s (a redrawing of) their graph, with NZ in all black.

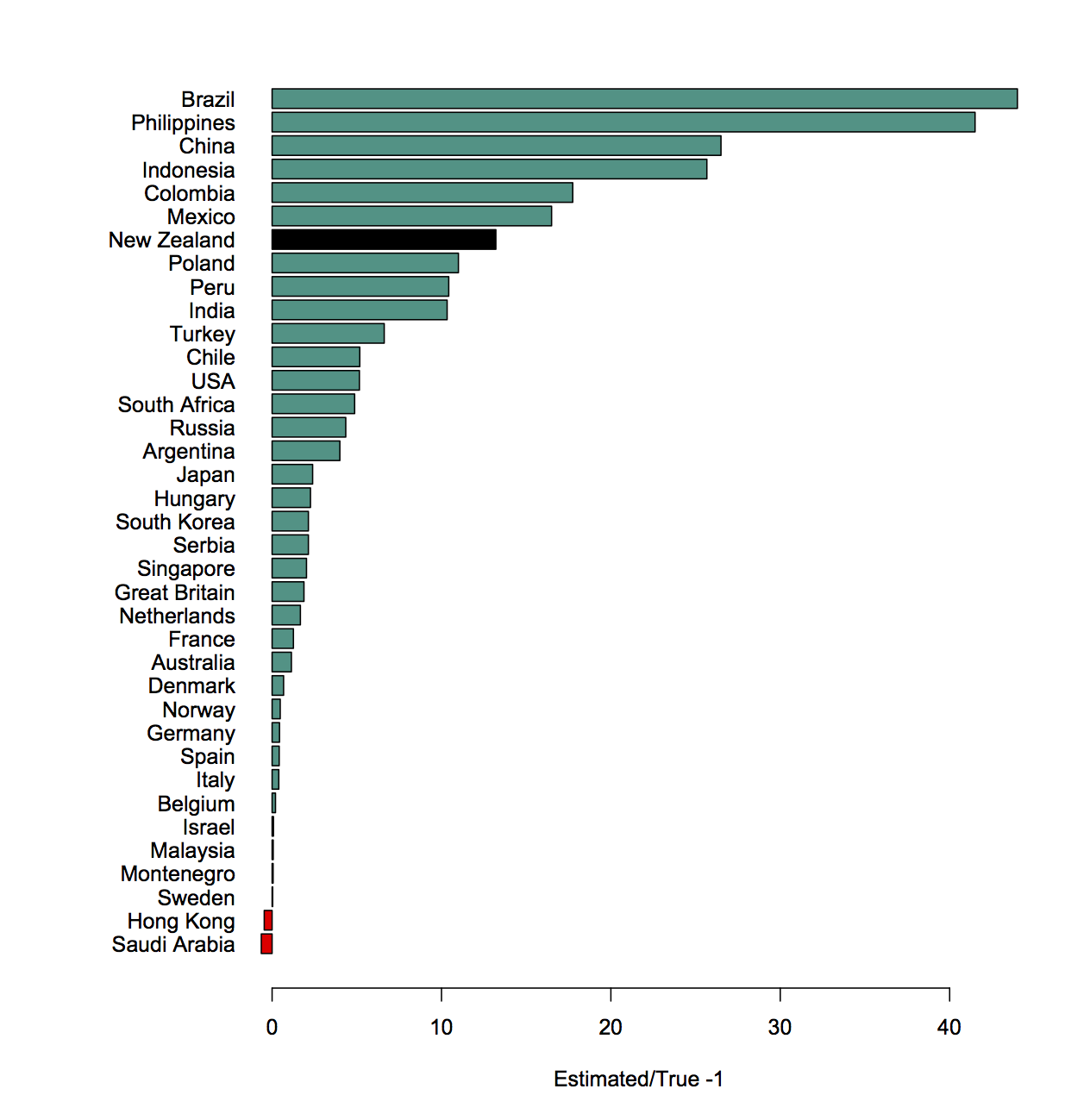

People think more than a quarter of NZ prisoners are immigrants; it’s actually less than 2%. I actually prefer this as a ratio

The ratio would be better on a logarithmic scale, but I don’t feel like doing that today since it doesn’t affect the main point of this pointpost.

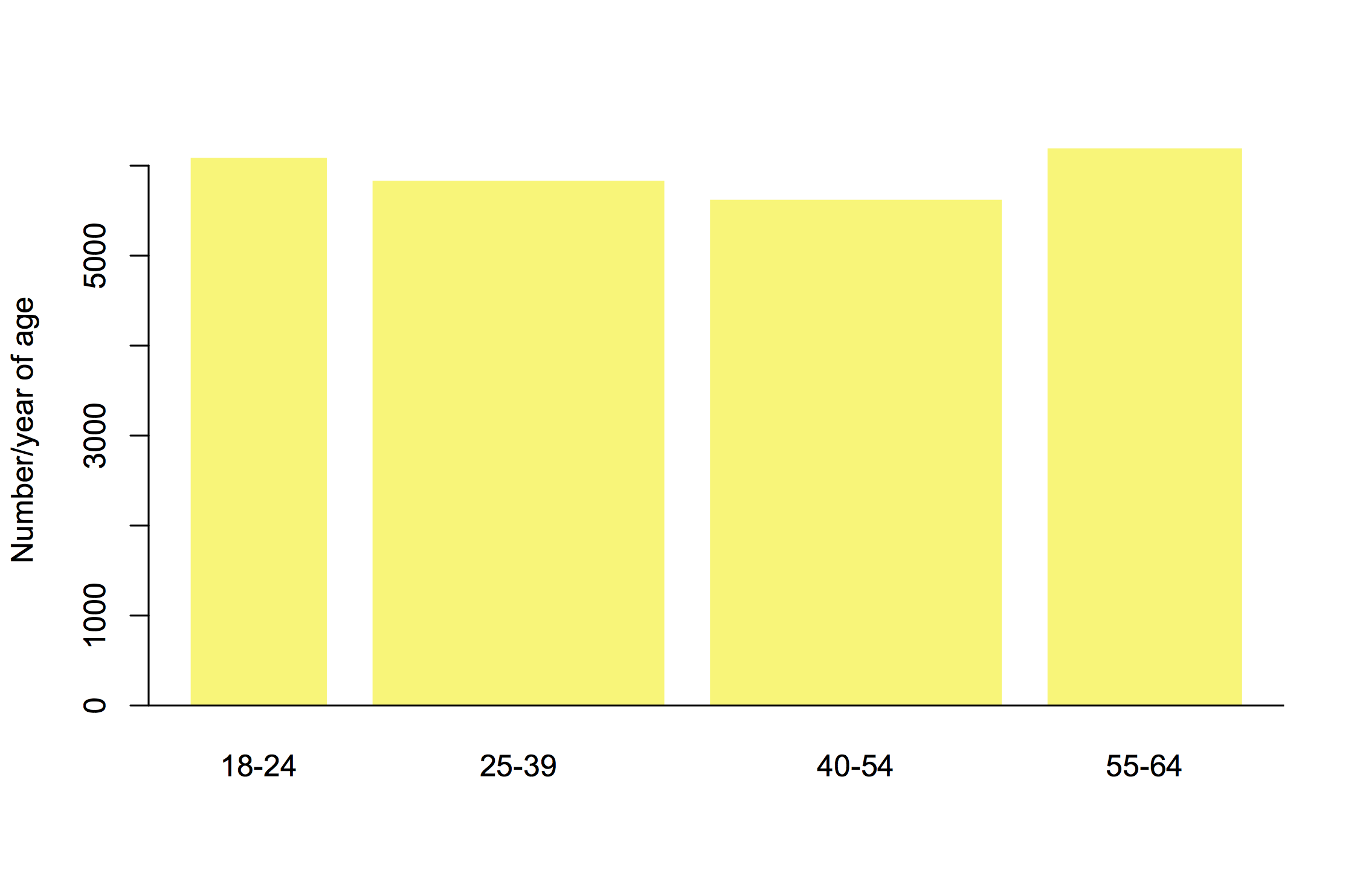

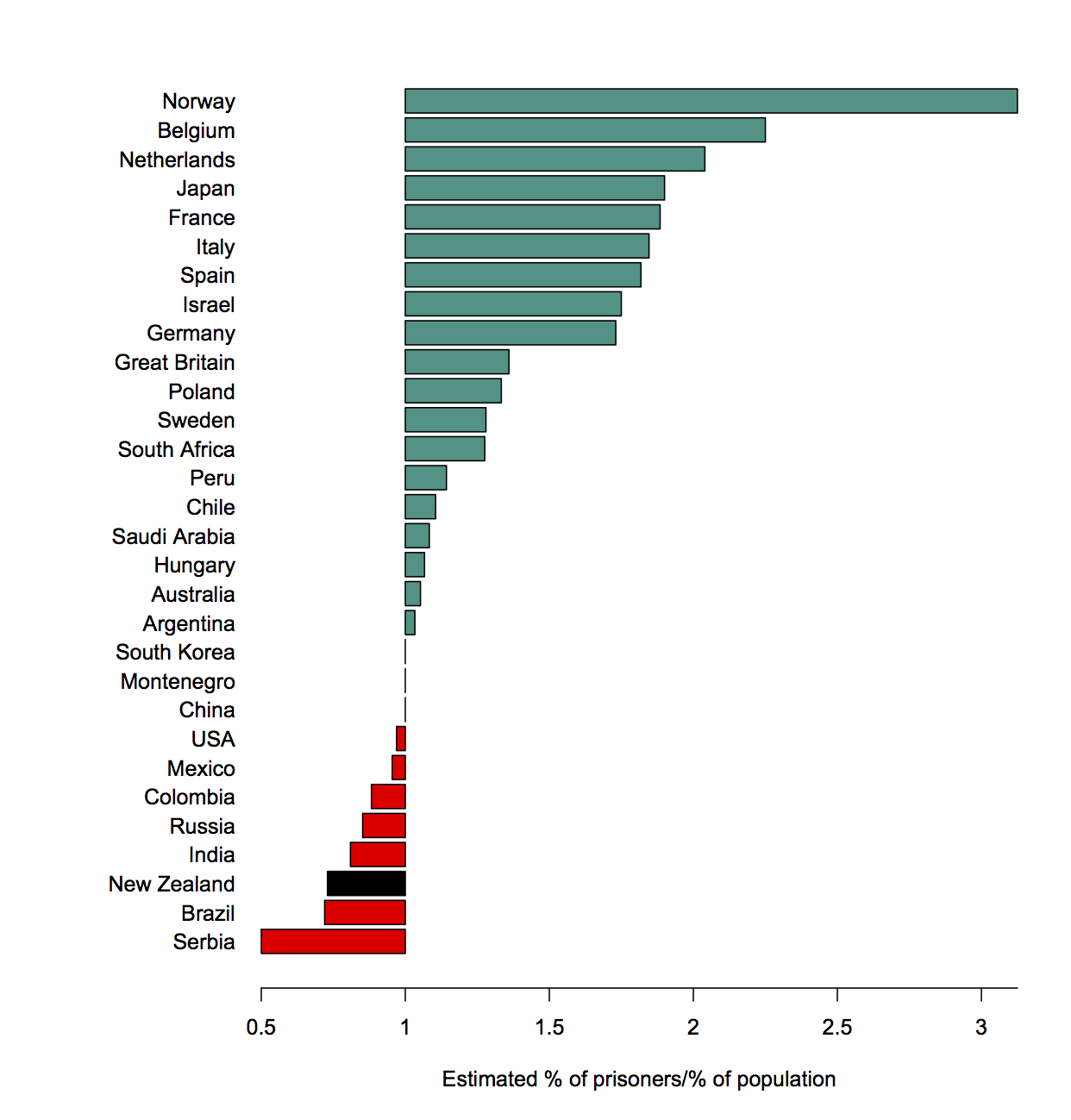

A couple of years ago, though, the question was about what proportion of the overall population were immigrants. That time people also overestimated a lot. We can ask how much of the overestimation for the prison question can be explained by people just thinking there are more immigrants than there really are.

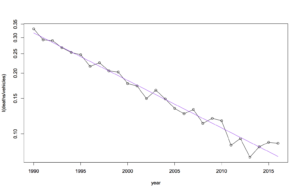

Here’s the ratio of the estimated proportion of immigrants among the prison population and the total population

The bar for New Zealand is to the left; New Zealand recognises that immigrants are less likely to be in prison than people born here. Well, the surveys taken two years apart are consistent with us recognising that, at least.

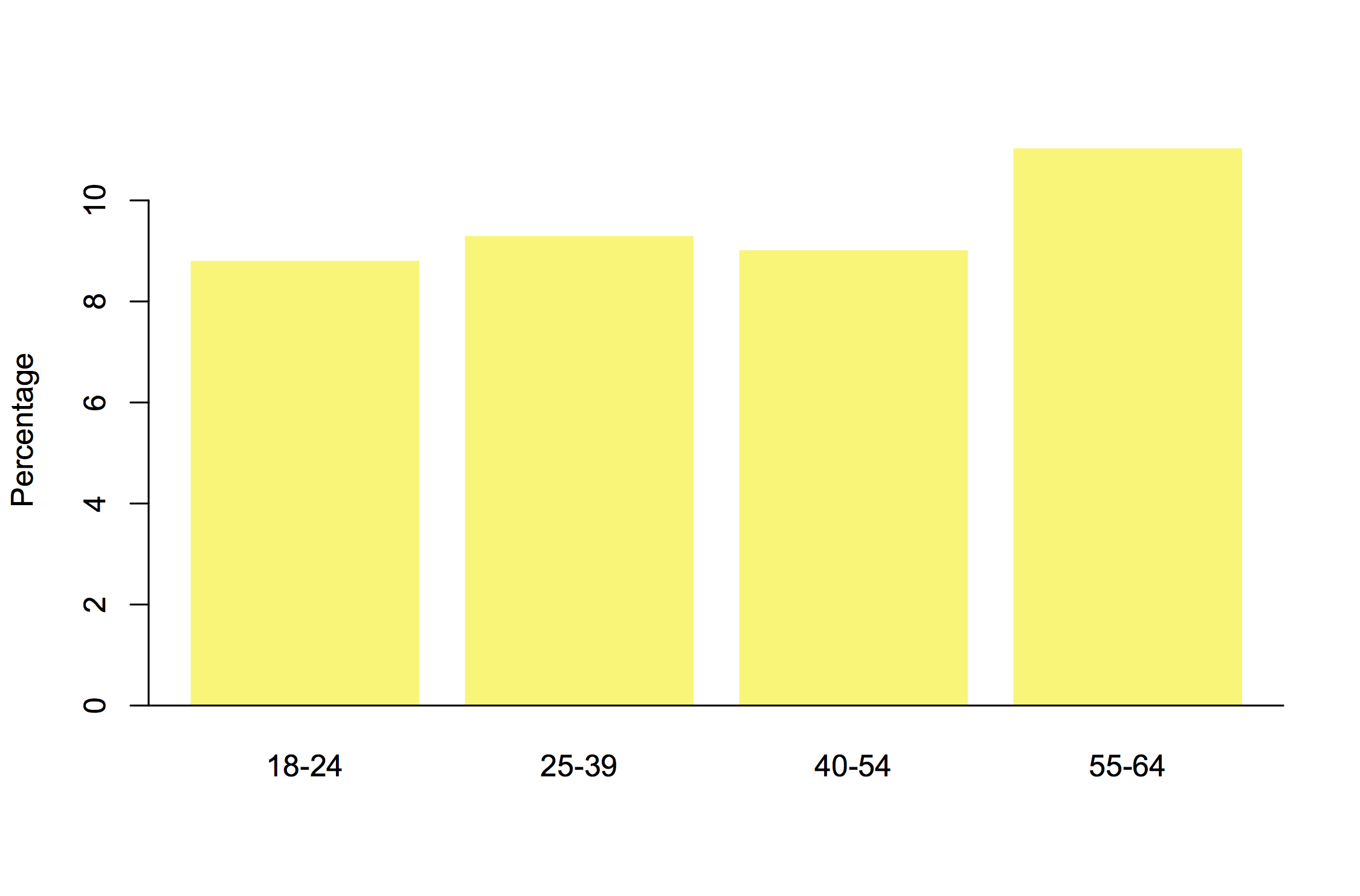

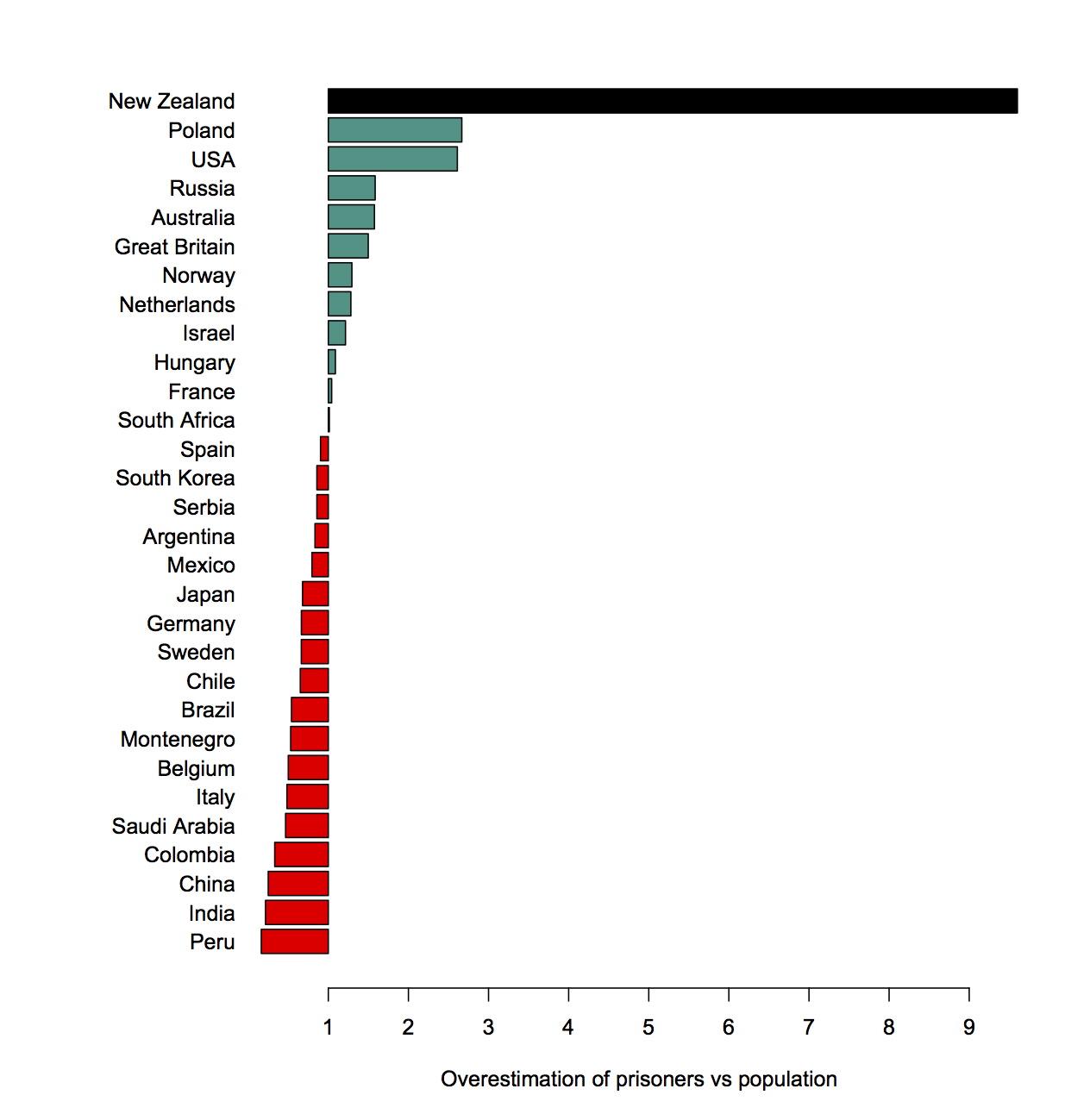

That’s just a ratio of two estimates. We can also compare to the reality. If we divide this ratio by the true ratio we find out how much more likely people think an individual immigrant is to end up in prison compared to how likely they really are.

It seems strange that NZ is suddenly at the top. What’s going on?

New Zealand has a lot of immigrants, and we only overestimate the actual number by about a half (we said 37%; it was 25% in 2017). But we overestimate the proportion among prisoners by a lot. That is, we get this year’s survey question badly wrong, but without even the excuse of being seriously deluded about how many immigrants there are.