This story didn’t get into the local media, but I’m writing about it because it illustrates the benefit of new statistical methods, something that’s often not visible to outsiders.

From a University of Otago press release about the work of A/Prof Suetonia Palmer

The University of Otago, Christchurch researcher together with a global team used innovative statistical analysis to compare hundreds of research studies on the effectiveness of blood-pressure-lowering drugs for patients with kidney disease and diabetes. The result: a one-stop-shop, evidence-based guide on which drugs are safe and effective.

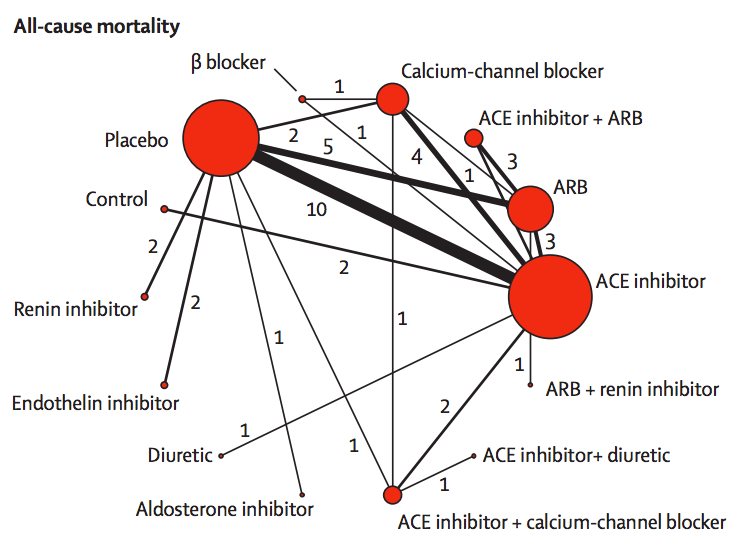

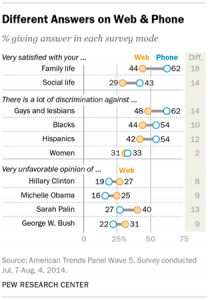

They link to the research paper, which has interesting looking graphics like this:

The red circles represent blood-pressuring lowering treatments that have been tested in patients with kidney disease and diabetes, with the lines indicating which comparisons have been done in randomised trials. The circle size shows how many trials have used a drug; the line width shows how many trials have compared a given pair of drugs.

If you want to compare, say, endothelin inhibitors with ACE inhibitors, there aren’t any direct trials. However, there are two trials comparing endothelin inhibitors to placebo, and ten trials comparing placebo to ACE inhibitors. If we estimate the advantage of endothelin inhibitors over placebo and subtract off the advantage of ACE inhibitors over placebo we will get an estimate of the advantage of endothelin inhibitors over ACE inhibitors.

More generally, if you want to compare any two treatments A and B, you look at all the paths in the network between A and B, add up differences along the path to get an estimate of the difference between A and B, then take a suitable weighted average of the estimates along different paths. This statistical technique is called ‘network meta-analysis’.

Two important technical questions remain: what is a suitable weighted average, and how can you tell if these different estimates are consistent with each other? The first question is relatively straightforward (though quite technical). The second question was initially the hard one. It could be for example, that the trials involving placebo had very different participants from the others, or that old trials had very different participants from recent trials, and their conclusions just could not be usefully combined.

The basic insight for examining consistency is that the same follow-the-path approach could be used to compare a treatment to itself. If you compare placebo to ACE inhibitors, ACE inhibitors to ARB, and ARB to placebo, there’s a path (a loop) that gives an estimate of how much better placebo is than placebo. We know the true difference is zero; we can see how large the estimated difference is.

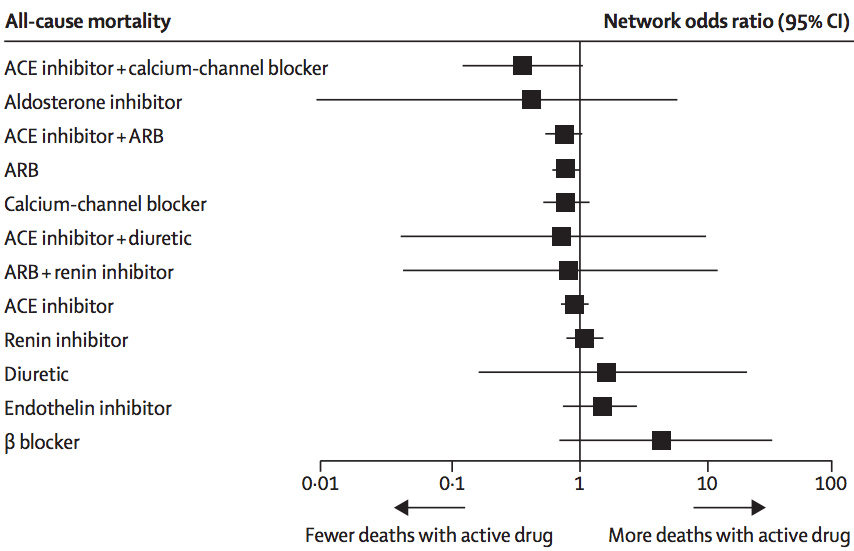

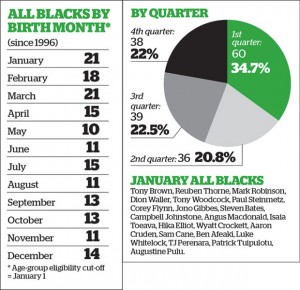

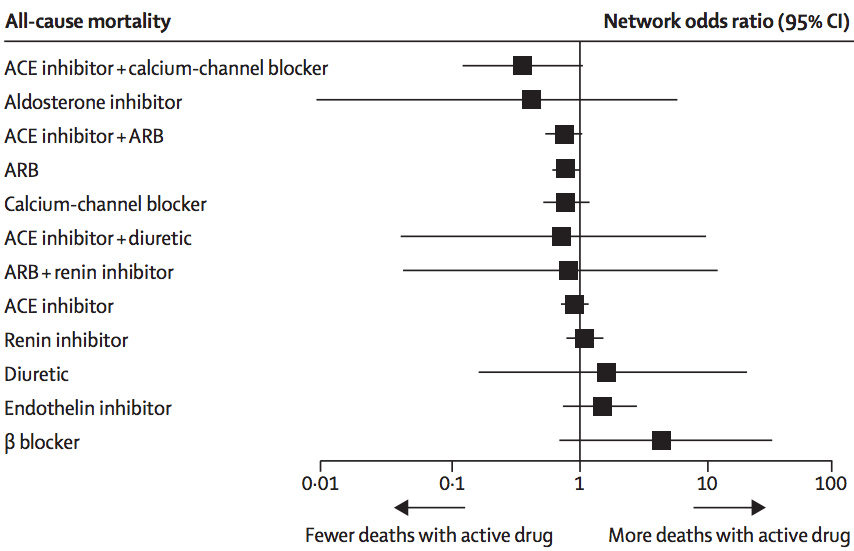

In this analysis, there wasn’t much evidence of inconsistency, and the researchers combined all the trials to get results like this:

The ‘forest plot’ shows how each treatment compares to placebo (vertical line) in terms of preventing death. We can’t be absolutely sure than any of them are better, but it definitely looks as though ACE inhibitors plus calcium-channel blockers or ARBs, and ARBs alone, are better. It could be that aldosterone inhibitors are much better, but also could be that they are worse. This sort of summary is useful as an input to clinical decisions, and also in deciding what research should be prioritised in the future.

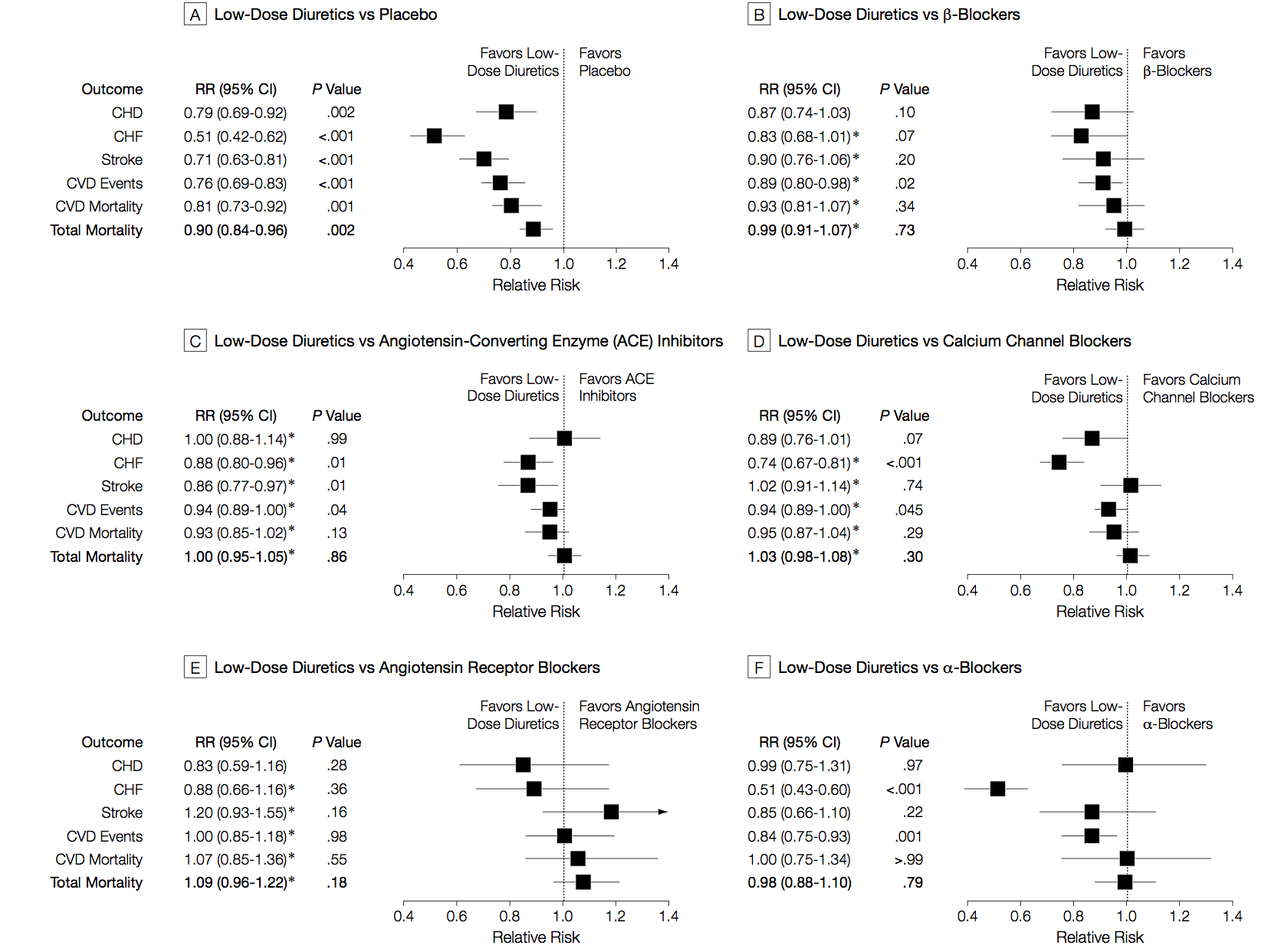

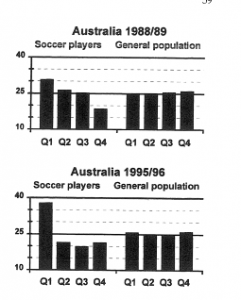

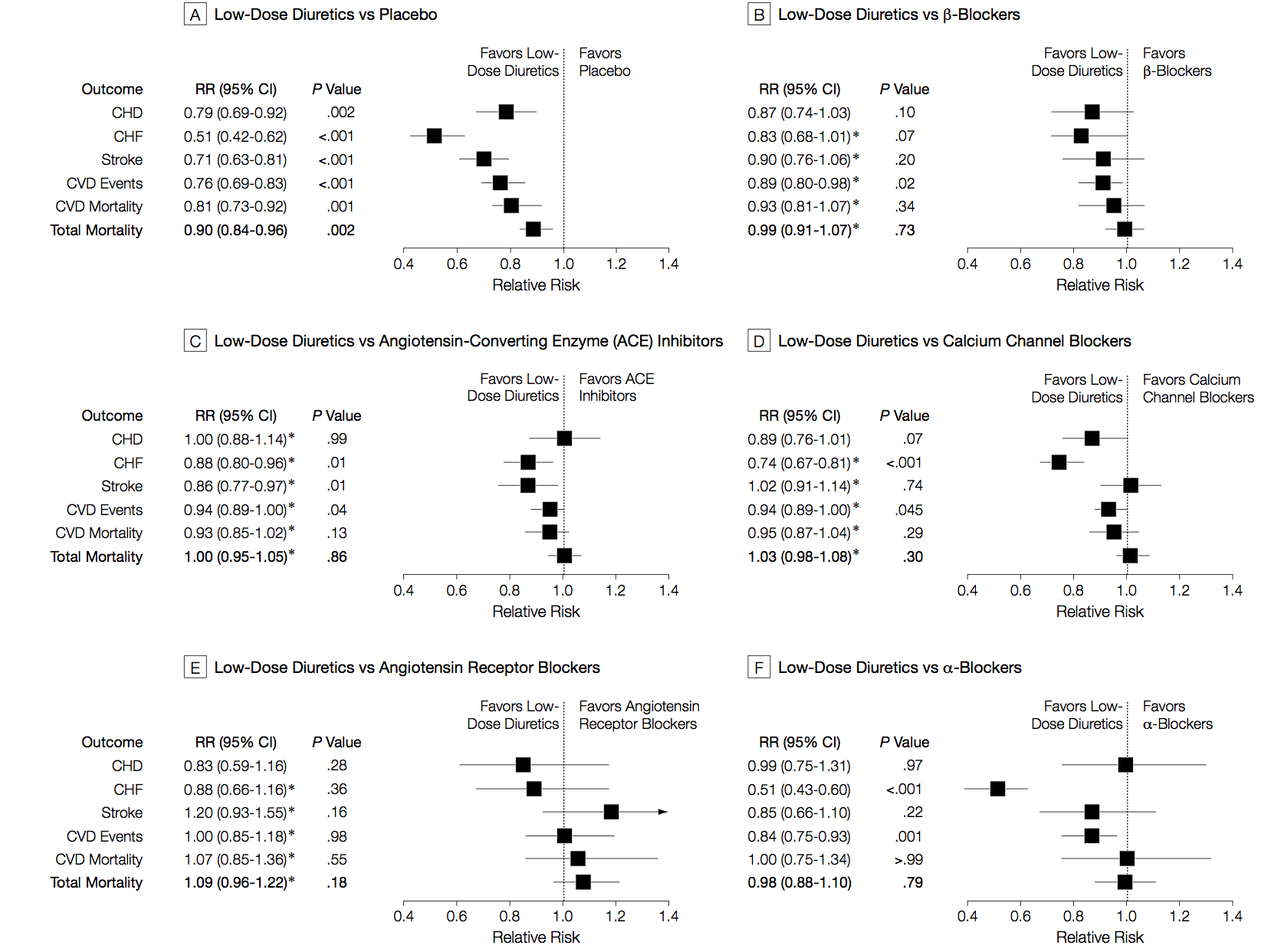

I said the analysis illustrated progress in statistical methods. Network meta-analysis isn’t completely new, and its first use was also in studying blood pressure drugs, but in healthy people rather than people with kidney disease. Here are those results

There are different patterns for which drug is best across the different events being studied (heart attack, stroke, death), and the overall patterns are different from those in kidney disease/diabetes. The basic analysis is similar; the improvements since this 2003 paper are more systematic and flexible ways of examining inconsistency, and new displays of the network of treatments.

‘Innovative statistical techniques’ are important, but the key to getting good results here is a mind-boggling amount of actual work. As Dr Palmer put it in a blog interview

Our techniques are still very labour intensive. A new medical question we’re working on involves 20-30 people on an international team, scanning 5000-6000 individual reports of medical trials, finding all the relevant papers, and entering data for about 100-600 reports by hand. We need to build an international partnership to make these kind of studies easier, cheaper, more efficient, and more relevant.

At this point, I should confess the self-promotion aspect of the post. I invented the term “network meta-analysis” and the idea of using loops in the network to assess inconsistency. Since then, there have been developments in statistical theory, especially by Guobing Lu and A E Ades in Bristol, who had already been working on other aspects of multiple-treatment analysis. There have also been improvements in usability and standardisation, thanks to Georgia Salanti and others in the Cochrane Collaboration ‘Comparing Multiple Interventions Methods Group’. In fact, network meta-analysis has grown up and left home to the extent that the original papers often don’t get referenced. And I’m fine with that. It’s how progress works.