The recently ex-kids are ok

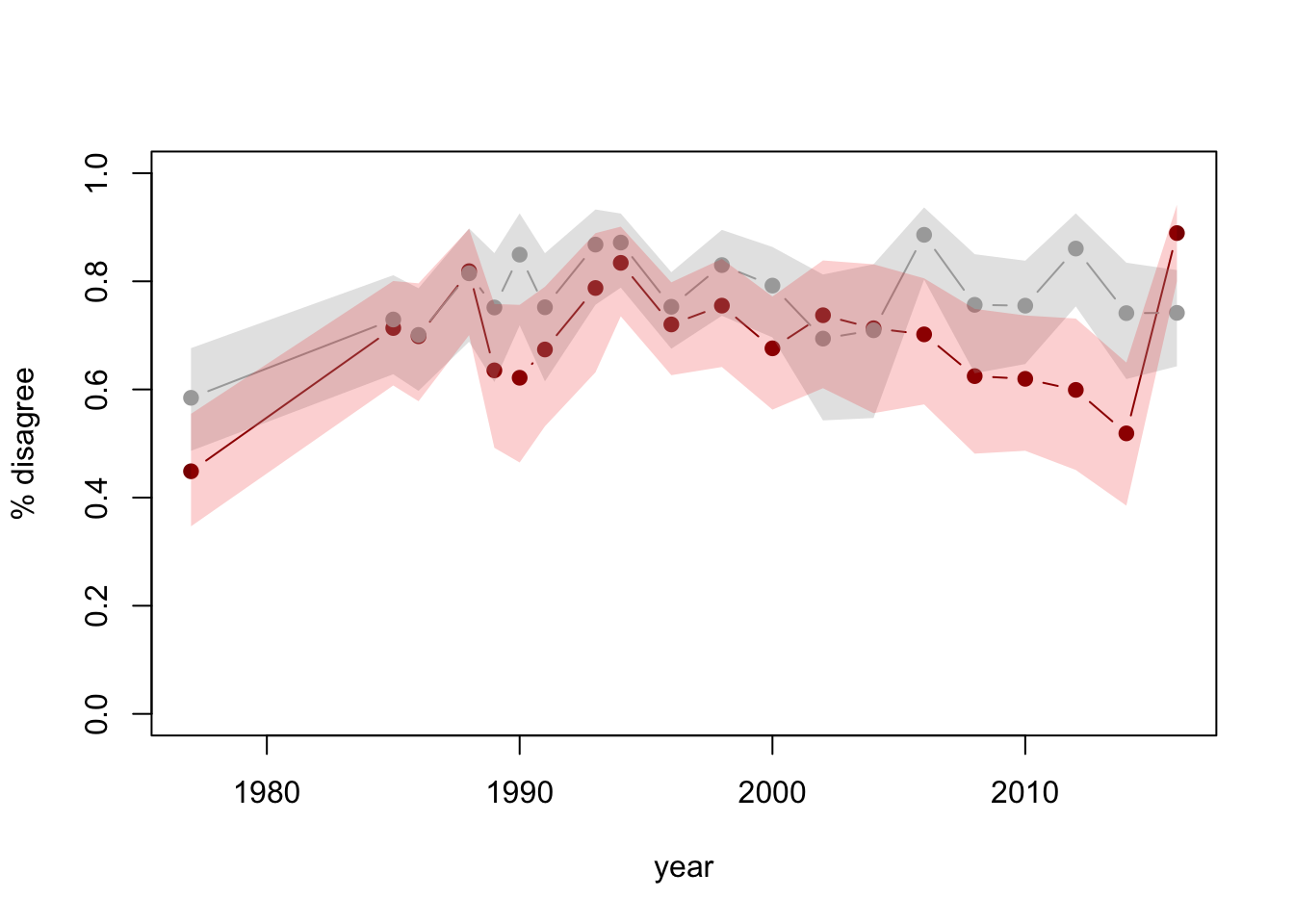

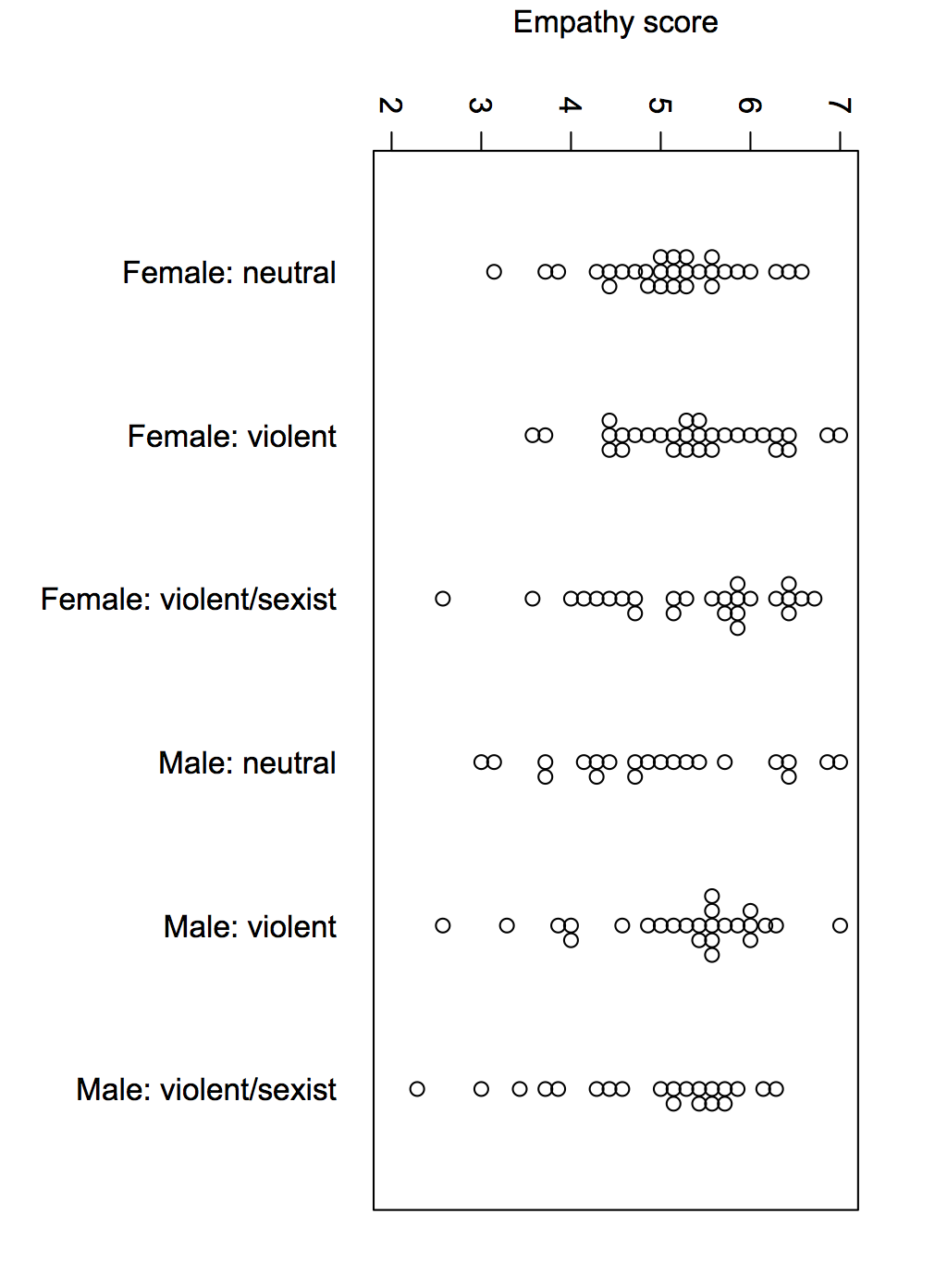

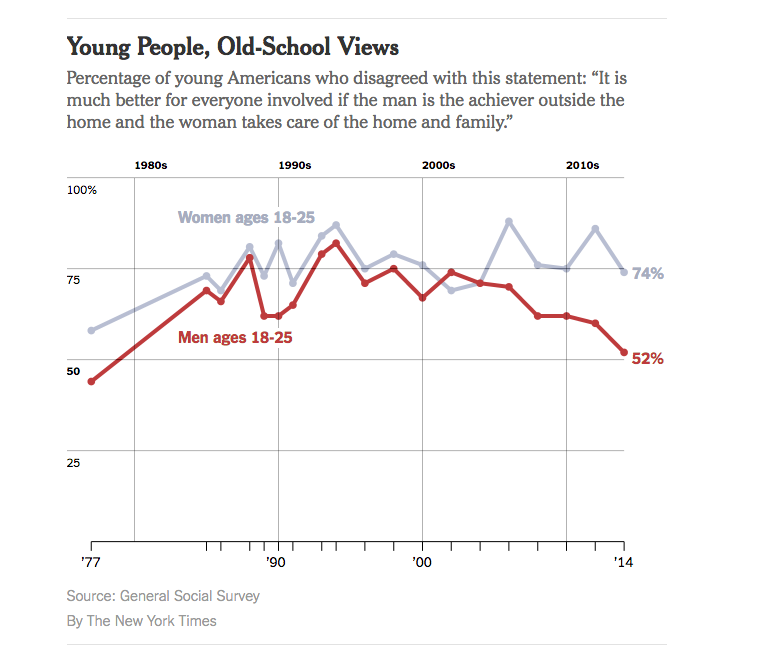

The New York Times had a story last week with the headline “Do Millennial Men Want Stay-at-Home Wives?”, and this depressing graph

But, the graph doesn’t have any uncertainty indications, and while the General Social Survey is well-designed, that’s a pretty small age group (and also, an idiosyncratic definition of ‘millennial’)

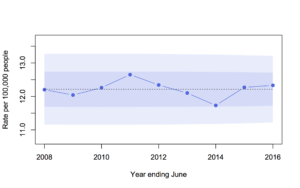

So, I looked up the data and drew a graph with confidence intervals (full code here)

See the last point? The 2016 data have recently been released. Adding a year of data and uncertainty indications makes it clear there’s less support for the conclusion that it looked.

Other people did similar things: Emily Beam has a long post including some context

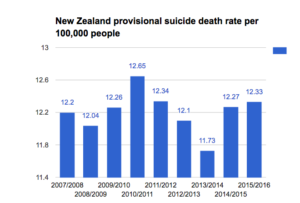

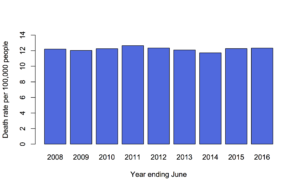

The Pepin and Cotter piece, in fact, presents two additional figures in direct contrast with the garbage millennial theory – in Monitoring the Future, millennial men’s support for women in the public sphere has plateaued, not fallen; and attitudes about women working have continued to improve, not worsen. Their conclusion is, therefore, that they find some evidence of a move away from gender equality – a nuance that’s since been lost in the discussion of their work.

and Kieran Healy tweeted

You may say every other sociologist in America did this yesterday, but I say I am doing my bit for reproducibility in social science. pic.twitter.com/Xdab692TK4

— Kieran Healy (@kjhealy) April 2, 2017

As a rule if you see survey data (especially on a small subset of the population) without any uncertainty displayed, be suspicious.

Also, it’s impressive how easy these sorts of analysis are with modern technology. They used to require serious computing, expensive software, and potentially some work to access the data. I did mine in an airport: commodity laptop, free WiFi, free software, user-friendly open-data archive. One reason that basic statistics training has become much more useful in the past few decades is that so many of the other barriers to DIY analysis have been removed.