Anybody for a slice of PISA?

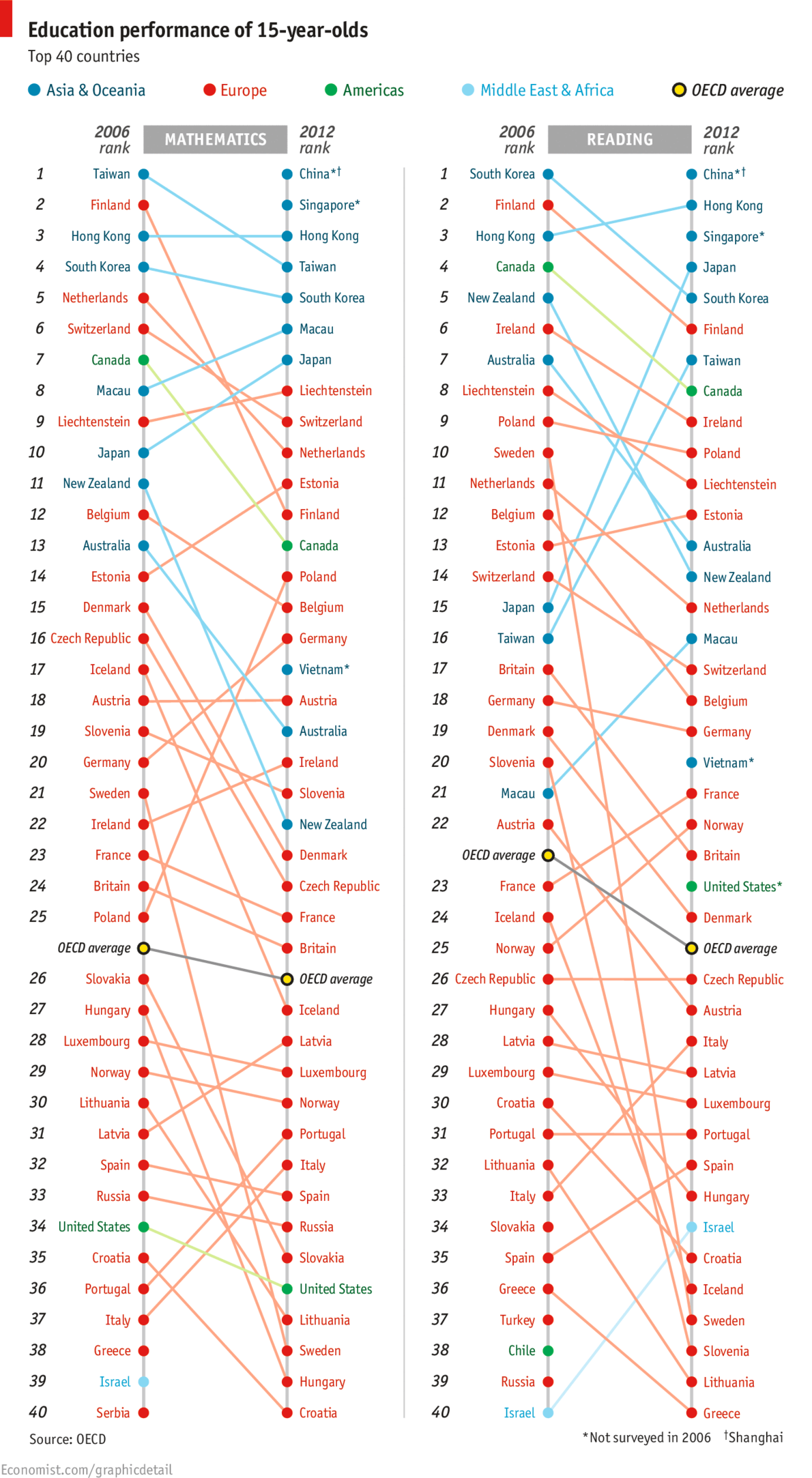

There has been significant coverage in the press of New Zealand’s slip in the OECD PISA (Programme for International Student Assessment) rankings for mathematics, reading, and science.

We probably should be concerned.

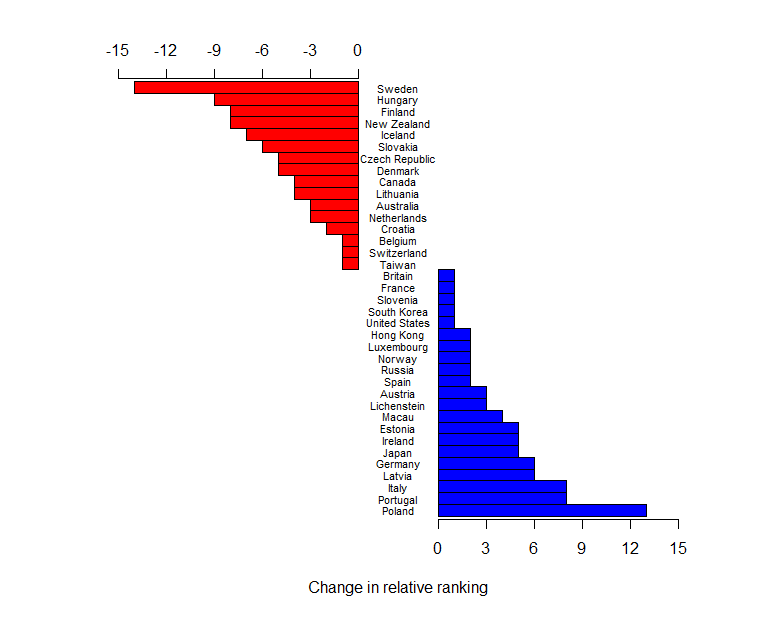

However, today I stumbled across the following chart:  in The Economist. Two things about it struck me. Firstly, part of the change (in the mathematics ranking at least) was driven by the addition of three countries/cities which did not participate in the 2006 round: Shanghai, Singapore, and Vietnam. The insertion of these countries is not enough to explain away New Zealand’s apparent drop, but it does move us from a change of down 11 places to a change of down 8 places. Secondly, I found it really hard to see what was going on in this graph. The colour coding does not help, because it reflects geographic location and the data is not grouped on this variable. Most of the emphasis is probably initially on the current ranking which one can easily see by just reading the right-hand ranked list from The Economist’s graphic. However, relative change is less easily discerned. It seems sensible, to me at least, to have a nice graphic that shows the changes as well. So here it is, again just for the mathematics ranking:

in The Economist. Two things about it struck me. Firstly, part of the change (in the mathematics ranking at least) was driven by the addition of three countries/cities which did not participate in the 2006 round: Shanghai, Singapore, and Vietnam. The insertion of these countries is not enough to explain away New Zealand’s apparent drop, but it does move us from a change of down 11 places to a change of down 8 places. Secondly, I found it really hard to see what was going on in this graph. The colour coding does not help, because it reflects geographic location and the data is not grouped on this variable. Most of the emphasis is probably initially on the current ranking which one can easily see by just reading the right-hand ranked list from The Economist’s graphic. However, relative change is less easily discerned. It seems sensible, to me at least, to have a nice graphic that shows the changes as well. So here it is, again just for the mathematics ranking:  .

.

The raw data (entered by me from the graph) has been re-ranked omitting Greece, Israel, and Serbia who did not participate in 2012, and China, Singapore, and Vietnam, who did not participate in 2006. I am happy to supply the R script to anyone who wants to change the spacing – I have run out of interest.

It is also worth noting that these rankings are done on mean scores of samples of pupils. PISA’s own reports have groups of populations that cannot be declared statistically significantly different (if you like to believe in such tests). This may also change the rankings.

Updates:

Professor Neville Davies, Director of the Royal Statistical Society’s Centre for Statistical Education, and Elliot Lawes, kindly sent me the following links:

Firstly a blog article from the ever-thoughtful Professor David Spiegelhalter: The problems with PISA statistical methods

and secondly, a couple of articles from the Listener, which I believe Julie Middleton has also mentioned in the comments:

Education rankings “flawed” by Catherine Woulfe” and Q&A with Andreas Schieicher also by Catherine Woulfe.