Some discussion on Twitter about political polling and whether political journalists understood the numbers led to the question:

If you poll 500 people, and candidate 1 is on 35% and candidate 2 is on 30%, what is the chance candidate 2 is really ahead?

That’s the wrong question. Well, no, actually it’s the right question, but it is underdetermined.

The difficulty is related to the ‘base-rate‘ problem in testing for rare diseases: it’s easy to work out the probability of the data given the way the world is, but you want the probability the world is a certain way given the data. These aren’t the same.

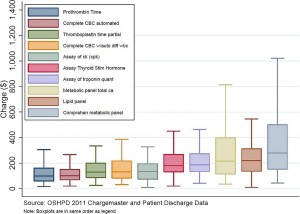

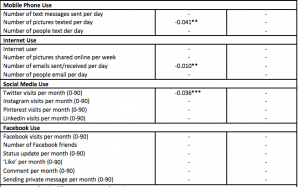

If you want to know how much variability there is in a poll, the usual ‘maximum margin of error’ is helpful. In theory, over a fairly wide range of true support, one poll in 20 will be off by more than this, half being too high and half being too low. In theory it’s 3% for 1000 people, 4.5% for 500. For minor parties, I’ve got a table here. In practice, the variability in NZ polls is larger than in theoretically perfect polls, but we’ll ignore that here.

If you want to know about change between two polls, the margin of error is about 1.4 times higher. If you want to know about difference between two candidates, the computations are trickier. When you can ignore other candidates and undecided voters, the margin of error is about twice the standard value, because a vote added to one side must be taken away from the other side, and so counts twice.

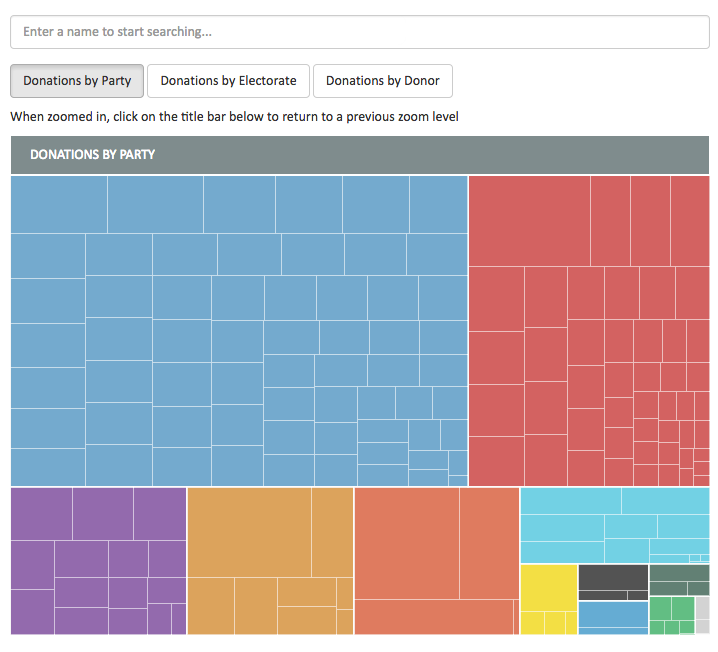

When you can’t ignore other candidates, the question isn’t exactly answerable without more information, but Jonathan Marshall has a nice app with results for one set of assumptions. Approximately, instead of the margin of error for the difference being (2*square root (1/N)) as in the simple case, you replace the 1 by the sum of the two candidate estimates, so (2*square root (0.35+0.30)/N). The margin of error is about 7%. If the support for the two candidates were equal, there would be about a 9% chance of seeing candidate 1 ahead of candidate 2 by at least 5%.

All this, though, doesn’t get you an answer to the question as originally posed.

If you poll 500 people, and candidate 1 is on 35% and candidate 2 is on 30%, what is the chance candidate 2 is really ahead?

This depends on what you knew in advance. If you had been reasonably confident that candidate 1 was behind candidate 2 in support you would be justified in believing that candidate 1 had been lucky, and assigning a relatively high probability that candidate 2 is really ahead. If you’d thought it was basically impossible for candidate 2 to even be close to candidate 1, you probably need to sit down quietly and re-evaluate your beliefs and the evidence they were based on.

The question is obviously looking for an answer in the setting where you don’t know anything else. In the general case this turns out to be, depending on your philosophy, either difficult to agree on or intrinsically meaningless. In special cases, we may be able to agree.

If

- for values within the margin of error, you had no strong belief that any value was more likely than any other

- there aren’t values outside the margin of error that you thought were much more likely than those inside

we can roughly approximate your prior beliefs by a flat distribution, and your posterior beliefs by a Normal distribution with mean at the observed data value and with standard error equal to the margin of error.

In that case, the probability of candidate 2 being ahead is 9%, the same answer as the reverse question. You could make a case that this was a reasonable way to report the result, at least if there weren’t any other polls and if the model was explicitly or implicitly agreed. When there are other polls, though, this becomes a less convincing argument.

TL;DR: The probability Winston is behind given that he polls 5% higher isn’t conceptually the same as the probability that he polls 5% higher given that he is behind. But, if we pretend to be in exactly the right state of quasi-ignorance, they come out to be the same number, and it’s roughly 1 in 10.